Ann Monka, was born in Lida, Poland in 1929 and was the youngest of three children born to Leon and Sarah Stolowitzky. Her family, including her older brother and sister, Michael and Bella, lived in a middle-class neighborhood in a wooden, three family home that belonged to her grandmother, who had 3 children and gave each of them an apartment. Ann attended a Jewish school from 1st through 5th grades where they spoke Hebrew, Polish and some Russian.

She was 10 years old when World War II broke out in 1939. At the time, there were 8,500 Jews in Lida. After heavy bombing in 1941, the Germans occupied Lida, and Ann’s home was burned down in front of her eyes. “One house after another went down in flames, we were homeless and didn’t know where to turn,” she reflected. Soon after, all Jews were forced to wear the identifying yellow Star of David, and were imprisoned in a ghetto.

After some time, the Nazis determined that there was not enough room for more than 10,000 people to continue residing in the small ghetto. They took some of the inhabitants out into a field, where mass graves were dug, and shot 6,700 of them. Ann lost aunts, uncles, cousins and her grandmother, whom she adored. Ann said, “As a child, I found it very difficult to understand what was happening.” Ann lived under German rule until 1943 when the second elimination began by putting the remaining Jews on trains headed for the Majdanek Concentration Camp and certain death.

To escape deportation, Ann, her mother and a cousin, hid in an attic above the brewery where her father had been employed as the controller. Although the Germans continued their search for the unaccounted-for Jews, they were never discovered. At the same time nearby, Ann’s father, brother and sister were shuttled onto a cattle car headed for the concentration camp. Her mother had no hope that they would ever see them again.

Shortly thereafter, Ann, her cousin Vela, and her mother left their hiding place and fled into the woods. “During this time, there was only one thing on our minds and that was to join the partisans,” she recalled. They wandered for eight days looking for the partisans and finally met a man who led them to a group of about 20 people. They slept under the trees, and berries were their main source of survival.

The partisans lived in constant danger that local informers would reveal their whereabouts to the Germans. Weeks went by without the Germans finding them. Life as a partisan in the forest was difficult because they had to constantly move from place to place to avoid being discovered. They raided farmers’ food supplies to eat and had to survive the winter in flimsy shelters built from logs and branches.

Meanwhile, Ann’s sister, brother and father had been loaded onto a cattle car headed for Majdanek. Her brother Michael, just 17 years old, maneuvered his way out of the window and was able to unlock the door to the train car. Of the 50 people crammed into the car, 11 of them jumped from the speeding train, seeing this risky move as their only chance at survival – among them, Michael, Bella and Leon.

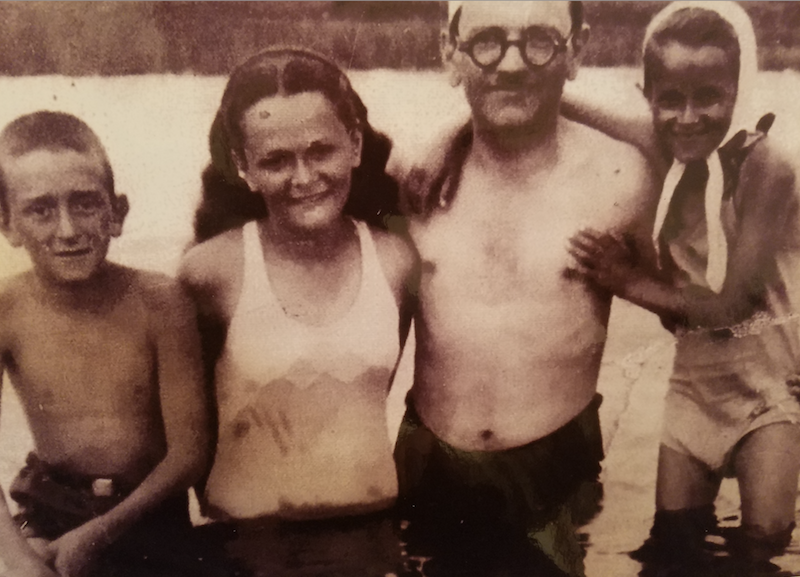

One morning, Ann woke up warm and content, and to her surprise saw her sister Bella in the distance. Incredibly, the three had survived their treacherous escape from the train and the entire family was reunited in the woods after three long months of separation and fearing one another dead. The entire Stolowitzky family lived with the Bielski partisan brigade in the Naliboki Forest, under the leadership of Tuvia Bielski.

While with the partisans, they built their own shelters and food was scarce, but their will to survive was amazingly strong. The Bielski Brigade was a “family camp” and different than most partisan groups. Most of the partisan groups consisted of single men; because their sole purpose was to fight and inflict as much damage as they could on the enemy. Their membership was limited to able-bodied men prepared for battle. Those unable to fight were left to fend for themselves.

What made the Bielski camp different than other partisan groups was the fact that this camp provided shelter for women, children and the elderly. In the confines of the camp, the fighters protected them all. Endowed with an unbreakable spirit, Ann regularly elevated the morale of her fellow partisans by entertaining them with her lovely voice, and with her powerful rendition of the Zog Nit Kein’mol (Hymn of the Partisans).

The Stolowitzky family was the one and only family unit that survived intact in the Bielski camp. The Bielski brothers saved 1,200 Jews from slaughter.

After spending two years in hiding with the Bielski partisans, the camp was liberated in December 1944 by Russian soldiers. Unfortunately, Ann and her family had nowhere to go. Their hometown of Lida had been burned and there was nothing there to return to. Her father decided to return to his original hometown of Lodz, Poland. He had not seen anyone since 1939 and upon arriving, sadly discovered that not one member of his family had survived. He had lost his father, mother, 3 brothers and 2 sisters, plus aunts, uncles and cousins.

Since no family member could be located and the conditions in Poland were dreadful, Ann’s parents thought their best chance would be to go to Palestine. However, they were faced with many obstacles. They tried to get papers allowing them to leave Poland and journey to Palestine, but the British, who were in control of Palestine at the time, refused them entrance. As a result, they left Poland by train and traveled to Czechoslovakia and then to Hungary. In Hungary, they learned of the Unra organization. Unra assisted survivors and set-up DP camps throughout Europe. With their help, Ann’s family received assistance and was sent to Austria. Life in the DP camp was paradise in comparison to the life they left behind in the woods. After some time, ORT set up trade schools for survivors and in 1947, Ann received a diploma in sewing.

Eventually, Ann’s family discovered that they had relatives in the United States. It took 4 years for the United States government to honor their family’s visa, but on November 21, 1949, 20-year-old Ann and her mother and father arrived in the US. Ann’s sewing degree proved to be very useful when she became the sole provider for her family. She was hired to work in a millenary factory and sewing hats became her trade.

Ann met Paul Monka, also a Holocaust survivor, in 1951 and they were married in 1952. They bought a business and through hard work realized the American dream. Ann and Paul had three children. Their oldest daughter, Rosalyn, taught school and Hebrew school; son, Ira, became a doctor; and youngest son Jay, took over his father’s business. Ann became a grandmother of 7 and a great-grandmother of 2.

Ann dedicated her life to teaching young people about the Holocaust and the importance of speaking out to prevent genocide by sharing her wartime experiences in schools and with community groups everywhere. She always ended her presentations with her rendition of the Hymn of the Partisans. Ann passed away on January 16, 2019.