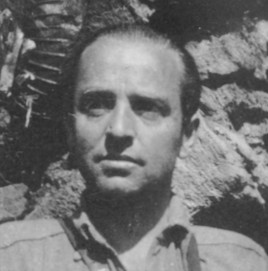

Avigdor Klimtka, a Jewish partisan who lived a brief but itinerant life, (from “Tag Eins [Day One]” as he used to say) was born in 1917 in Austria, the illegitimate child of a mother who had been raped, in Lida, Belarus, by an anti-Semitic Russian officer who threatened to kill her. Avigdor’s mother died shortly after giving birth, and Avigdor lived for a time with a German-speaking nun, and was eventually given to a family of Jews in the vicinity of the Polish town Ivie.

When the Nazis occupied Ivie in 1941, Avigdor’s knowledge of both German and Russian, in addition to, of course, Yiddish, gave him many advantages. He managed to procure several arms for himself, first by killing a German officer, and then by boldly wearing the officer’s suit and going to a German garrison, where he easily gained entry and emerged with a cache of more than a dozen weapons, along with information on Nazi plans and troop movements. He was the type of man who was constantly trying to prove himself, and – with the loss of his mother, and his insecurity about his background (his surname was given to him by the nun who took care of both him in Austria) – he often took chances, and was always on the move.

For a time he worked with partisans in the Russian otriad, Iskra, but always on the fringes, and only for a brief time before he moved on to another group – or to action on his own, or with one or two trusted friends. His specialty was weapons, and he was always more than willing to give a gun to a partisan in need, so he was seldom without friends. He helped blow up two trains loaded with ammunition and war material, and then one other train he did completely on his own, but not before he ran off with an armload of ammo almost immediately before the explosion went off. Unfortunately, he received shrapnel injuries to his arms, legs, and groin region, and nearly died from blood loss in a ditch close to the tracks. Eventually, a fellow partisan who had worked with him months before found him.

Most of the bleeding had come from a vein or an artery in his left leg, and the injuries to his arms were superficial, but eventually the injuries to his groin region became infected after initially healing somewhat. One of the partisans had a white powder, probably some type of sulfanilamide, that he had found in a first-aid kit, and there were apparently some sulfa drug tablets in the same kit, that Avigdor used to eventually heal enough to fight again, but he would never again be up to his true fighting form.

After the war, he very much wanted to come to the United States, but he had a hard time getting passage on a ship, and finally ended up in Buenos Aires. From there he went to Mexico, and eventually crossed the border into Texas. From there he made his way up the rails to Tennessee, Virginia, and South Carolina.

He said he’d lived so long in the woods, and on the fringes, that the last thing he wanted to do was to go to New York City, where he would most likely have been sure to find many kindred souls. Many in the Jewish community helped him in the South, though, but since the sulfa drugs had either not fully done their job, or perhaps they had masked some sort of slow infection, he eventually required surgery. He was in Charleston, South Carolina at the time, and Dr. Leon Banov performed the surgery and saved his life, although the groin injuries had most likely spread irreversible damage to his immune system, so he spent much of the rest of his life either in and out of hospitals or recovering in the homes of friends he made along the way. One of Leon’s relatives, Abel Banov, helped him on numerous occasions. Dr. John Cannon, another friend, also helped on at least one occasion. Rosabel Blank assisted in finding a place for him. Abel’s friends Lee and Bessie Orr, in Marion, Virginia, personally helped on several occasions.

Since (practically) nobody could say his name in America, he changed “Klimtka” to “Cline,” and went by “Bob” rather than “Avigdor,” but even though his English was quite passable, he had such a heavy accent that he was instantly branded as an outsider in what was, at the time, an area of the South that was anything but friendly to “his type.” In Marion, a part of Smyth County, there was considerable racism of all types, and he was appalled at how he saw so many black people mistreated. The Orrs held him back more than once from stepping in when, for instance, he witnessed black people being beaten for nothing worse than walking on the wrong part of the sidewalk, or saying hello to a white person.

Some of the Jim Crow laws were so indecipherable that virtually no one could figure them out, not even the whites, so, as a result, most whites simply made up the rules as they went along. Avigdor worked for a while at the Lincoln Theater in downtown Marion. The theater was strictly segregated, with the blacks at the back of the balcony, and one night a gang of whites caught a white teenager, Willis Lee, and falsely accused him of raping a white woman. They were going to lynch the boy, and Avigdor intervened. The boy escaped, but Avigdor was badly beaten. He was punched in the face, stomach and groin, and died a few weeks later, in 1947, from the groin injuries. Lee and Bessie Orr helped care for him. Avigdor said to them, “They always told me America was the Land of the Free, but what I saw at the Lincoln is not the type of thing I’d expect to see in such a land.”

At the same time, Avigdor still had great respect for America, and one of his proudest moments was when Dr. Cannon introduced him to his Congressman uncle, Clarence Cannon. Clarence autographed a photo, and Avigdor carried it with him the rest of his life. Another of the highlights of his life was being able to see papers from the once-famous American author, Sherwood Anderson, who had, in his later years, lived in Marion, and who had published two newspapers there. Bessie Orr had been a friend of Sherwood’s, and had numerous memorabilia that she showed to Avigdor. The South was a sweet-and-sour place to live, though, and racism often reared its ugly head at the most inopportune moment. For instance, Avignor used to read aloud to Maggie Trail, Bessie’s blind sister, but when her parents found out about it – and about the fact that Avigdor was Jewish – they put an end to it. Susie Trail, the mother, had herself had a “run-in” with a black man in the past, and there had been a lynching on a nearby property as a result. What Avigdor learned about the South sometimes made him very sad, but he was so in love with the freedom he experienced in the woods in the area, that he continued to live in the South. From time to time he made a few excursions outside of the region, and he stayed with John Burns in Connecticut. He traveled briefly about other parts of the Eastern part of the United States, to such places as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Buffalo, and for a while the Macri family in Pennsylvania helped him out, allowing him to do chores for room and board, that is, until they found out he was Jewish, and then he had to move on. He met Anya Bilica, one of Abel’s acquaintances, and spoke Russian to her on various occasions. He found a few friends with whom he could speak German, too, and often sang a partially-Germanized version of the “Hymn of the Jewish Partisans,” parts of which went something like the following, per notes left by Maggie Trail:

Sag nicht das du geyst dem letzten weg,

Durch himlen blayene farshtele blose teg.

[Don’t say you’re walking your final road,

Though leaden skies cover days of blue.]…

Und von wo du gefalen bist a shpritz fun unzer blut,

Unsere Mut wachst wiedermal

[Wherever a spurt of our blood has fallen to the ground,

Our courage will sprout again.]…