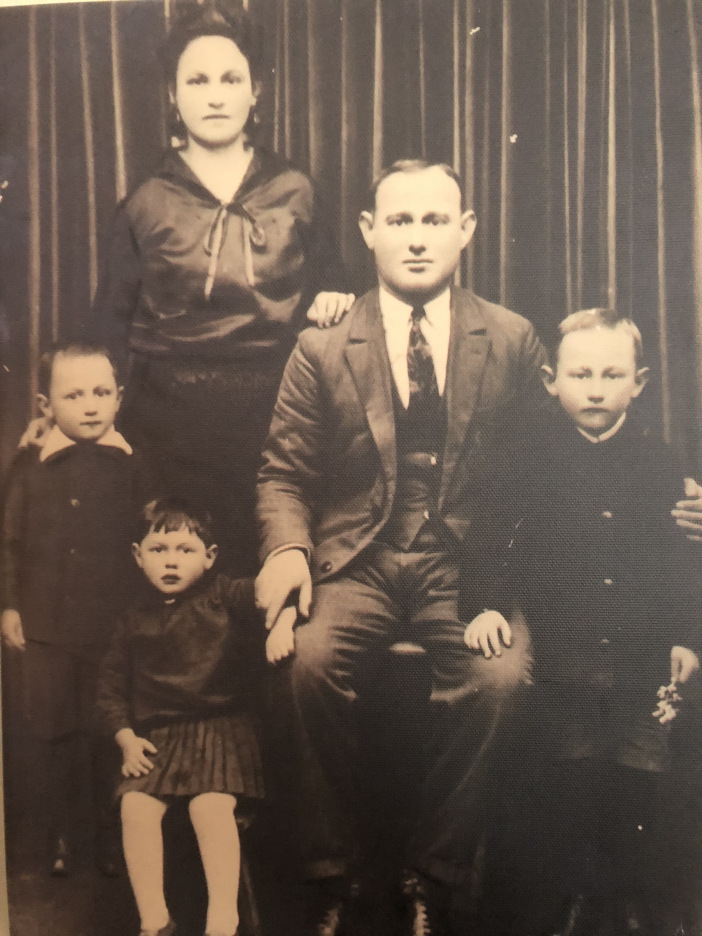

David Bakst was born to a loving Jewish family in Ivie, Poland (modern-day Belarus) on December 15, 1922. He had three siblings: Eliyahu (“Ellie”) (born 1924), Batya (born 1927), and Gussie (born 1932).

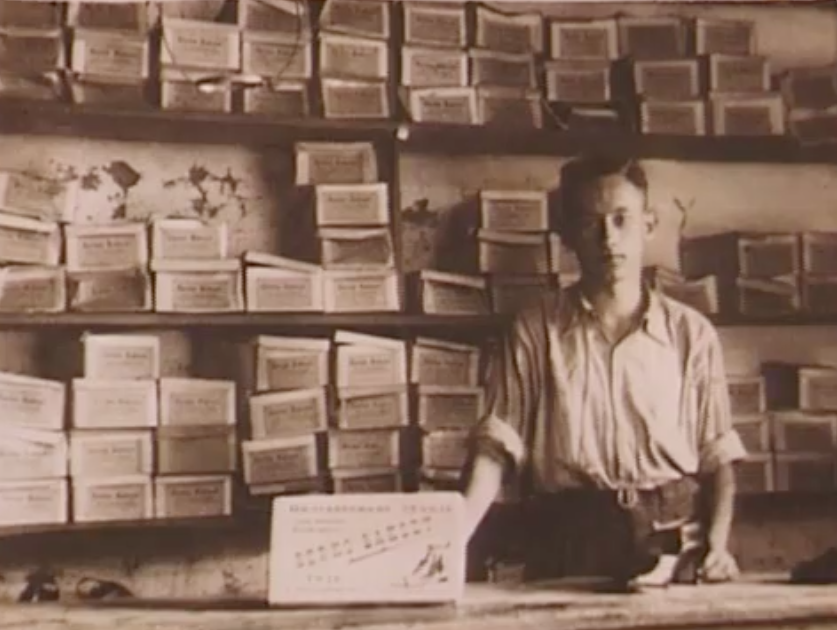

The Bakst children attended one of the multiple local Jewish schools. On evenings and weekends, they were often found playing, studying, and spending time with family. In the wintertime David frequently ice skated on the town lake, and he played volleyball in the warmer months. During his school lunch break, David enjoyed working in his father’s shoe store, which was the largest supplier of handmade leather shoes in the region. Beryl Bakst’s shoemaking business grew rapidly, employing many local men and earning Beryl financial success and the respect of locals, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

As orthodox Jews, the Baksts observed the Sabbath each week, including sharing elaborate meals prepared by Beryl’s wife, Rochel. They attended regular synagogue services, hosting their extended family for lunch afterward as well as for seders and other holiday meals. Rochel gave tzedakah (charity) regularly, helping to buy groceries for the less well off when she visited the town market each week. She was pioneering in serving as not only a wife and mother of four children but also a worker in her husband’s store.

In September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Ivie. Beryl’s business was confiscated, and the Bakst family was targeted for being capitalists. The family went from wealthy to impoverished overnight. David and Ellie’s plans to attend university were thwarted, and all four children suddenly became outcasts. The family lived in constant fear of being deported to Siberia, and Beryl was frequently tortured by NKVD agents seeking to learn more about his business practices.

While Beryl managed to keep his family fed by offering some hidden valuables to farmers in the area, the situation grew increasingly untenable as German forces began bombing Ivie in June 1942. By the following month, the Germans had occupied the town. They immediately put the Jews of Ivie to work, forcing them to labor from dawn to dusk in the brutal summer heat with minimal food and water. Many were murdered—shot in the streets for working too slowly or in one of the multiple mass killings—before the remainder were herded into a ghetto.

Beryl, desperate to insulate his family from the Nazis, came up with a plan. He understood that leather was extremely valuable to the soldiers and told a few Germans that he could produce it for them in a nearby abandoned factory if he were allotted a small workforce and leave to travel for supplies. The Germans agreed.

Each morning, Beryl led his family and some additional Jewish workers from the Ivie Ghetto to the factory where they made the leather. Free from the watchful eyes of the Germans, Beryl visited his former business associates who provided—either out of pity or in exchange for leather goods—information on the war and food for Beryl’s workforce. When the Jews returned to the ghetto at night, the guards were greeted with a slightly smaller workforce but extra offerings of leather to ignore the discrepancy. Beryl used the factory as a guise to escape dozens of Ivie Jews to partisan groups operating in the nearby Naliboki forest.

While the factory protected the Baksts, Beryl understood that their refuge was temporary. As rumors of an impending Aktion percolated, Beryl attempted to escape his family to the Bielski partisans in late 1942. Unfortunately, brutal winter temperatures were too much for little Gussie to bear, and most of the family returned to Ivie within a few days. Ellie Bakst remained with the Bielskis, where he was shot and killed by the Nazis while on a mission in early January 1943. That same month, the Germans liquidated the entire Ivie Ghetto, shooting many and sending the remainder to meet a similar fate in Borisov. The town was declared Judenrein, with only seventeen Jewish lives spared: the Jews working in Beryl’s factory.

After the liquidation, Beryl’s workforce was relocated to a small house nearby to the factory. Knowing that the Nazis could come for them at any time, Beryl decided that it would be safer for the Baksts to split up. He paid a local farmer to hide Rochel, Gussie, and some cousins in a bunker under the floorboards of a barn. But someone tipped the Germans off about the hideaway, and they set the barn ablaze, killing everyone inside.

Not long after, the Nazis surrounded the leather making factory apprehending most of the remaining workforce. David managed to escape, avoiding the gunfire that pursued him. He found his father at their designated emergency meeting spot with a look of despair painted on his face.

Batya had been captured and Beryl was prepared to turn himself in, hoping to save her. David pleaded with his father not to return. With tears streaming down their faces, David told his father that going to the Germans would only do them a favor. Beryl saw no alternative. “I am a father, I have to do it,” he told David. “But you are a father to me too!” David demanded. After much begging, David convinced his father that the best chance of saving Batya was to go to the partisans.

Beryl and David joined the Iskra partisans operating in the nearby forest. The group was a Russian unit, and though they were reluctant to accept Jews, David’s physical fitness and Beryl’s leather making abilities proved a worthy addition. David was assigned to the role of a fighter, responsible for sabotage missions against the German. He and his comrades spent their days ambushing German trucks with gunfire and blowing up trains and bridges. The partisans’ attacks hampered the supply of critical goods to the German front, and provided a means for the partisans to amass the undamaged weaponry and food.

The Iskra partisans relied on local Poles who provided valuable information and supplies. Through this network, David and Beryl discovered that Batya was alive and imprisoned in a work camp making leather in the nearby city of Lida. The partisans had an agent—Mr. Yankevich—who was willing to assist with a rescue mission for a payoff. David and Beryl worked with the man to develop a plan. A few days later, Mr. Yankevich, armed with a coat to cover Batya’s yellow star and falsified identity papers, walked Batya through the German checkpoint and out the prison gate.

Upon her reunion with David and Beryl, Batya became one of few women adopted into the Iskra partisans. She spent her days cooking food for the group, repurposing whatever measly scraps they found into a meal. Not long after, the partisans discovered that Mr. Yankevich was a double agent providing information to the Nazis on partisan activities. He had performed Batya’s rescue to gain the partisans’ trust. A few Iskra fighters killed him in retaliation.

In July 1944, the area was liberated. David was conscripted into the Soviet Army, leaving his father and sister behind in Lida. David was assigned to the front and ordered to march all day every day across the continent until his legs gave out. Eventually, they reached the battlefield, where David was tasked with laying and repairing cable wires to maintain communication networks. On multiple occasions he barely escaped the jaws of death, finding himself severely concussed and with bullet holes piercing the pleats of his coat, just missing his body.

After meeting the American allies in Magdeburg, Germany in April 1945, David returned to his family in Poland. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration transported the Baksts to Ranshofen, a Displaced Persons camp in Austria just a few miles from Hitler’s birthplace. At Ranshofen, David met his future wife, Paula Silberfarb, who immigrated to Cuba with her surviving mother and siblings. Batya and her husband—whom she met in the partisans—attempted to immigrate to Palestine, but were captured en route and interned in Cyprus until Israel declared independence.

David and Beryl were determined to move to New York where Beryl’s brothers lived, but America’s antisemitic quotas made obtaining immigration visas challenging. The pair relocated to a different Displaced Persons camp in Hofgeismar, Germany, hoping it would provide an easier path to the United States. As they waited for an update on their immigration status, Beryl underwent hernia surgery, wanting to enter the United States physically fit and able to work. He died of complications shortly thereafter.

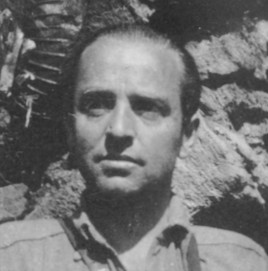

David, entirely alone and depressed, eventually was granted a visa in late 1948. In New York, he was taken in by extended family, working long days at his Uncle Willie’s pickle factory and taking English classes at night. Though he could hardly make ends meet, David saved a few dollars each week to call Paula and eventually to visit her in Cuba. In 1950, the couple married in Havana’s main synagogue.

Paula and David relocated to a small apartment in New York City, where David worked his way up from rolling pickle barrels to running an enormous deli meat distribution company, supplying most major grocers in the New York City region. They raised four children and were proud to have put them all through college and one through medical school, before retiring upstate in the late 1980s to be closer to their grandchildren.

David was an adoring grandfather. He watched his grandchildren several days per week and attended every graduation, grandparents’ day, and school play. David was also heavily involved in his local community, becoming a Gabbi at his temple, running daily prayer services in his neighborhood, and serving as vice president of his homeowner’s association. He was a talented musician, performing in several musicals and teaching himself to play the mandolin. David was unwavering in his positive attitude, passion for Judaism, and devotion to his family.

David passed away peacefully on December 22, 2020, near his winter home in Florida, shortly after his ninety-eighth birthday. He is survived by his wife of over seventy years, four children, four grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter. His biography, The Shoemaker’s Son, is authored by his granddaughter Laura Bakst and will be released in the fall of 2021.