Henryk Lubelski was born in Dabrowa Gornicza, Poland on August 23, 1911. He was raised in a religious Jewish family and his parents, Yehudah and Sarah, emphasized the importance of education. Henryk’s father was a cantor and a shochet (ritual slaughterer). In 1916, the Lubelskis moved to Rawicz, a town in German-occupied Poland. Henryk was first in his class in secondary school, where he also excelled in wrestling and soccer. After graduating, Henryk became an apprentice in the meat business.

In 1935, Henryk’s father secured a position in the city of Katowice, Poland, where Henryk worked in the sausage business. Because Katowice was near the German border, Henryk spoke fluent German along with Polish and Yiddish. When the war broke out in September 1939, Henryk fled from Katowice and traveled east towards the USSR. However, uncertain if conditions for the Jews would be any better, he decided to turn back. His route took him through many small Polish towns, where he took shelter with the Jewish people who were still there.

In 1942, Henryk was in Kolomyja, Poland, when the Germans established a ghetto. In the ghetto, Henryk met his future wife, Elizabeth Buchsbaum. Elizabeth was born on December 9, 1920, in Stebnik, Poland, and was raised in Budapest, Hungary. Although Henryk and Elizabeth were seeing other people, sparks soon grew between them. Henryk worked in the ghetto kitchen and, when it was Elizabeth’s turn in line, he would serve her from the bottom of the pot, giving her a more filling and nutritious cup.

As conditions worsened, Elizabeth’s parents pooled their resources and paid a smuggler to take their daughter out of the ghetto. Later that year, the ghetto was liquidated. Henryk and four friends made a plan ahead of time; if the Germans were going to shoot them in the woods they would scatter, and if they were loaded onto trains they would jump.

The Jews of Kolomyja were soon rounded up for mass deportation. As they were forced onto the cattle cars, an indelible memory was stamped into Henryk’s mind. Non-Jews lined up to watch their neighbors being taken to their deaths. In front of Henryk, a young Jewish woman was holding her baby. At the last moment, she handed her baby to a stranger in the crowd. “Can anyone imagine what was going through that mother’s mind and heart as she did that?” Henryk would always wonder.

It was a long and terrible journey as everyone was shoved tightly together. The train finally made a stop, and a bucket of water was brought to Henryk’s train car. “Nobody is going to be drinking any of that water,” he told a friend. His friend was incredulous. “How could you say that? They haven’t had anything to drink for days!” But Henryk was sadly right. The frantic people pulled the bucket every which way, and all the precious water was spilled and wasted.

Henryk carried a saw blade in his boot and looked for an opportunity to escape once he was in the cattle car. There was a loose board, and he sawed a hole big enough for him and his friends to jump through. Before leaping from the moving train, Elizabeth’s parents asked Henryk if he survived the war, to please find their daughter and give her their blessing. He promised to do so and he fulfilled his word.

After jumping, and breaking his hand upon impact, Henryk hid in peasants’ barns with one of his friends before they were discovered by the Hungarian police. They were taken to Tolonhaz Prison where Henryk met Henry Armin Herzog and Mietek (Mieczyslaw) Kuczera who became his friends and comrades.

The three friends were soon moved to Csorgo Internalo Tabor, a smaller Hungarian prison. When they heard that there would be a deportation of Jews back to Poland in May 1944, Henryk and Herzog acted quickly, certain that deportation would be a death sentence. They decided that taking their own lives was preferable to going back to blood-stained Poland. Henryk swallowed benzene and Herzog cut his wrist, landing them in the prison hospital. Nonetheless, they survived and were sent to the infirmary. When they were recuperated enough, they tied sheets together and escaped from the second-floor window.

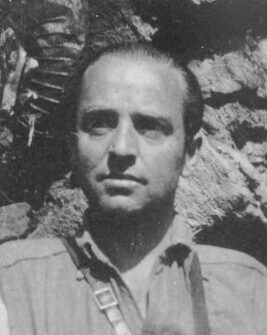

Earlier, Mietek had been caught attempting to escape the ghetto but had managed to escape his captors. The three friends fled through Slovakia until reaching the Tatra Mountains in the summer of 1944 in search of partisans. From their vantage point in the mountains, they spotted a picturesque village surrounded by forests. The peacefulness was suddenly torn asunder by machine-gun fire. From their hiding place, they saw a sight they had long dreamed of: SS soldiers with their hands raised in surrender to partisans. The Russian partisans called for fighters to take guns from the Germans’ trucks. Henryk, Herzog, and Mietrak didn’t think twice before each grabbing a rifle.

As the Russian commander ordered the soldiers to get off their trucks, the Nazis made a run for the village. The commander opened fire. Henryk, Herzog, and Mietek joined in the shooting, avenging the deaths of their parents, relatives, and friends. The commander welcomed them into his group as official partisans. As they proceeded higher into the mountains, the road became too narrow for their trucks. The commander ordered the remaining Germans to be shot and for gasoline to be poured on their trucks. Henryk and his friends helped themselves to grenades and ammunition from the trucks and set them on fire. During his time with the Russian partisans, Henryk experienced antisemitism within the ranks but stayed strong despite the prejudice. However, compared to the Polish partisans, the Russians were much less antisemitic.

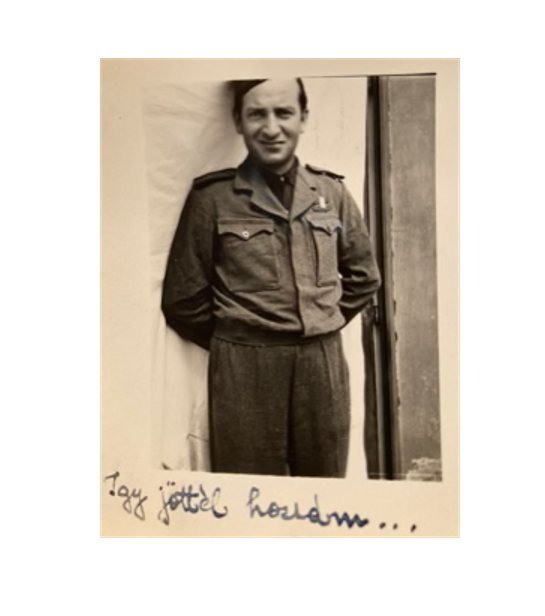

In August 1944, the Germans invaded Slovakia from all directions, supported by tanks and planes. The area of Spis and the city of Kežmarok were soon taken. Henryk, Herzog, and Mietek met three Jewish refugees from Bochnia, near Krakow. Among them were two former soldiers who had served in the Polish Army, Józef Jakubowicz and Kargul. They had formed a volunteer Free Poland unit to serve with the Free Czechoslovak Army and asked Henryk, Herzog, and Mietek to join them. Henryk and his friends were sworn in as a Polish unit of the 1st Czechoslovak Army before being taken to their barracks and issued uniforms and weapons. As a partisan, Henryk sabotaged the Germans by supplying Soviet troops with information about German artillery positions.

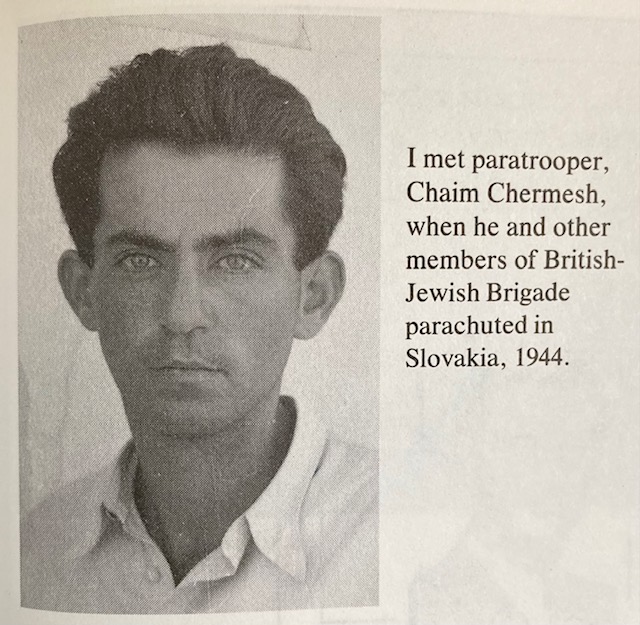

One exciting surprise was in store for the three. They were told by the Slovak Jews in town that a group of Jewish paratroopers from Palestine, who had volunteered to parachute into occupied Europe, were dropped into Slovakia near Banská Bystrica and wanted to meet them. It was an unforgettable moment when they met three men, including Chaim Chermesh, and one woman, Hannah Szenes, wearing British uniforms with a Palestine shoulder patch.

In October 1944, the Germans captured Zvolen, and the partisan forces were ordered to evacuate Banská Bystrica. All fighting men and civilians began fleeing to the Niske Tatry Mountains. The group numbered seventy-five soldiers and refugees, mostly men, along with Mrs. Frieder, the wife of the Chief Rabbi of Slovakia, and her children.

One day, German planes appeared and strafed the group with their machine guns. Everyone ran for cover on the exposed road, some finding shelter under a bridge. The dead were mingled with the wounded, and the medics were unable to cope with so much work. Henry, Herzog, and Mietek were unhurt but as they went around covering bodies, they came upon the bodies of Mrs. Frieder and her daughter. Her little boy, Gideon, was standing next to them crying.

After a week in the frigid mountains with seven-year-old Gideon Frieder, it was obvious that the men couldn’t care for him properly. Henryk, Herzog, Mietek, and another man, Stefan, took turns carrying the boy as they journeyed toward a village to find him a home. They spotted light from a hut in a small, remote village at the foot of the mountain. They placed the boy in the care of a Catholic shoemaker and his wife who sheltered the boy for six months before he was reunited with his father. Gideon Frieder later became a noted scientist and government official who worked for the Ministry of Defense in Israel.

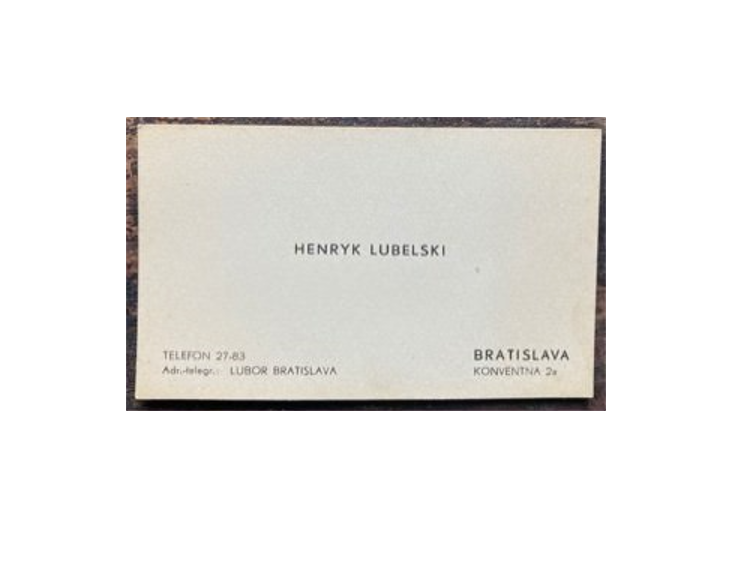

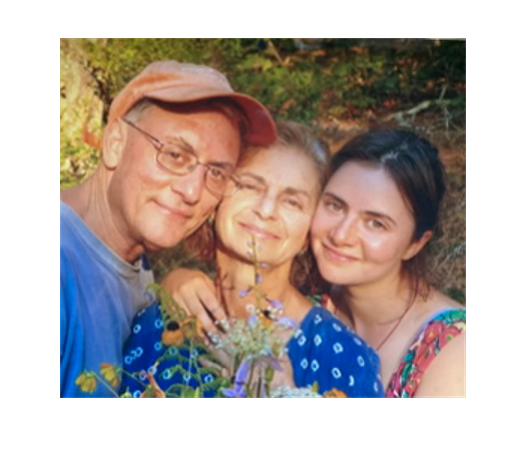

After the war, Henryk managed to find Elizabeth who was living in Budapest. She didn’t recognize him at first and thought he was a Russian soldier. However, after realizing it was Henryk, she knew in an instant that her struggle was over. Henryk and Elizabeth were soon married and lived in Bratislava, Slovakia, where Henryk sold sausage casings on the black market. They moved to Vienna and were about to put a deposit on an apartment when the Polish quota for passage to the USA opened. In November 1950, they arrived in Peekskill, New York, where Elizabeth’s brother and sister-in-law were residing. Henryk and Elizabeth’s daughter, Barbara, was born a few months later. Their second child, Irwin, was born in 1954.

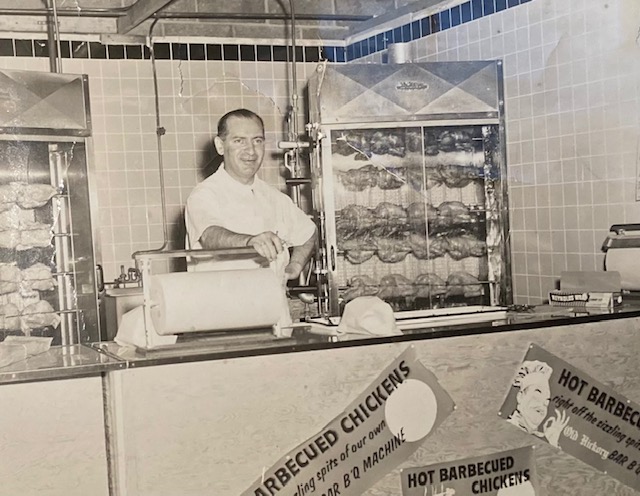

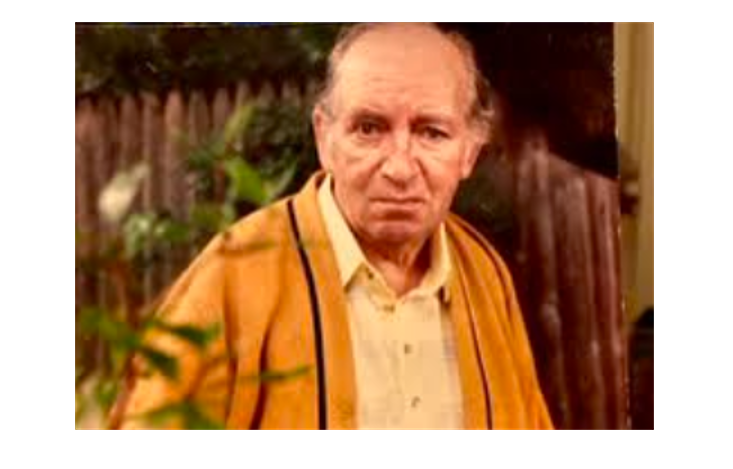

Henryk Lubelski went by the name of Henry Lubell in the United States. In Peekskill, NY, he worked in a variety of jobs including in a dressmaking factory and selling rotisserie chickens at a weekend market in New Jersey. He ran a newspaper delivery service for many years with his brother-in-law, Harry Brooks (Buchsbaum). It was hard work in the rain or shine, but he provided a good life for his family. People adored Henry. He was a kind man, a great father, and had a wonderfully dry sense of humor. When asked in an interview by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Who liberated you?” Henry responded, “I liberated myself!” Although he was far from being a boastful person, Henry was proud of having fought with the partisans.

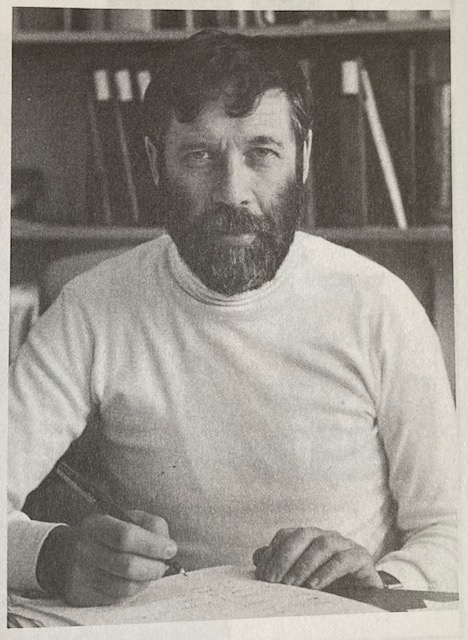

After the war, Henry stayed in touch with his friend, Herzog, who wrote a spellbinding book about his Holocaust experiences entitled And Heaven Shed No Tears. The book includes many episodes with Henry from their time with the partisans from which information for this biography was gained.

Henry Lubell had an accident on Rosh Hashana in 1993 and fell into a coma. Like only the very righteous, he died nine days later on Kol Nidre Night at the age of 82.

![IMG_1537[1] IMG_1537[1]](https://www.jewishpartisancommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/IMG_15371-e1626273803730.jpg)

![IMG_1563[1] IMG_1563[1]](https://www.jewishpartisancommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/IMG_15631-e1626274182822.jpg)