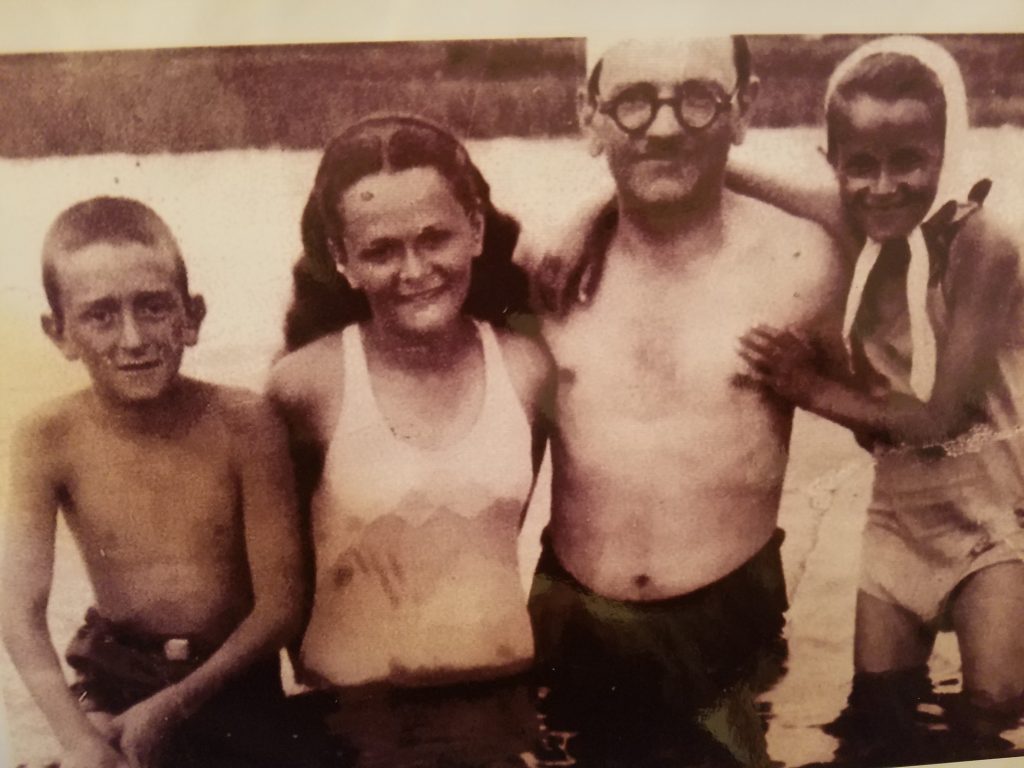

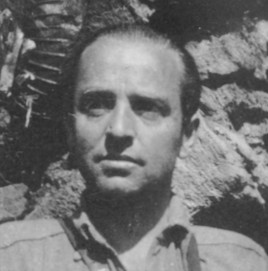

Michael Stoll (Stolowitzky) was born on February 21, 1926, in Lida, Poland to parents Leon Stolowitzky, an accountant, and Sarah Stolowitzky. He had an older sister, Bella, and a younger sister, Ann. His family lived in a farmhouse with three wings with his grandmother, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Michael was particularly close with his younger cousin Vivian. Michael’s father worked at the local brewery in Lida. Michael attended a private school where he received an education in Hebrew. His family spoke Yiddish and kept a kosher home. Lida had a strong and vibrant Jewish cultural life; Yeshivas, a Jewish library, and many Jewish organizations. Michael’s family would host guests from local Yeshivas for Shabbos.

In 1939, the Jewish population of Lida numbered roughly 8,500 people. In the summer of 1939, the Russians entered and occupied Lida. When his father Leon was drafted into the Polish army, the war truly began for Michael. Under Russian occupation, food, clothing, and other essential items became commodities. In addition, the Russians imposed strict rules in Lida, including closing the Hebrew schools and forcing Jewish children to attend Russian schools. Six months after being drafted and serving as a prisoner of war in Russia, Michael’s father returned to Lida to work in the brewery. People in town who favored socialism reported him for being a Zionist. Zionism was considered counter-revolutionary and anti-Russian, and Leon faced interrogation for months. However intense and brutal the Russian occupation was, the family was not prepared for the future under German occupation.

The Russians stayed in Lida until June of 1941 when Germany bombarded Lida. Michael and his family were forced from their home early one morning while sleeping and fled to the lake down their street. The town, including their home, mainly was built of wood, and the town was set ablaze. When the family returned to their home in the afternoon, it and their beloved town were destroyed. Michael and his family fled to the outskirts of town and lived with his extended family until the ghetto was created. Amazingly, the Pupko brewery, where Leon had worked, survived the bombardment. Michael’s father went back to work at the brewery and his family ended up living in the brewery along with six or seven other families. In the meantime, the ghettos of Lida were being formed, and slowly Jews from smaller towns were brought there. Jews were forced to wear yellow Stars of David, and a Judenrat, a Jewish ghetto militia, was formed.

On May 8, 1942, the Lida ghetto was emptied. People were segregated based on their ability to work or not. Around 6,700 people who could not work, such as the elderly and children, were brought to a field and killed with machine guns. Michael and his family had been told by an engineer in the brewery what would happen beforehand and were told to hide in the brewery. Michael heard the screams and the sound of machine guns in the night. The brewery was spared. Michael would later discover he had lost many family members that night: his grandmother, aunts, uncles, and two cousins. One of Michael’s uncles (Vivian’s father) died because he would not leave his parents, who were killed.

On September 15, 1943, while Michael was working in the brewery, SS officers brought the Jewish men to the local jail, where they were accused of poisoning the beer. Michael was only 17 at the time. Michael and his father, along with the other men, were taken to the train station. There, Michael and Leon were reunited with Michael’s sister Bella, but Michael did not know where his mother, sister Ann or cousin Vivian were. Vivian’s mother, who had hidden elsewhere, was found by the police and was sent to the Majdanek death camp.

Michael, Leon, and Bella were boarded on the train, told they were being sent to a work camp, and to remain calm. However, the word on the train was that they were headed to Majdanek, a death camp where they would be slaughtered immediately. So they made a plan to escape. Bella was able to get an ax from a Polish policeman whom she had known in high school.

At just 17 years old, Michael bravely helped his family and many others on that train car escape. They broke the bars of the window with the ax to create an opening. Michael then climbed through the small window and inched his way on a sliver of track for 10-12 feet while the train was traveling at about 40 miles per hour. He broke the wired and sealed latch with his bare hands and opened the door from the outside, allowing some people to jump out before the police began shooting towards the train, and Michael was forced to close the door, now being back on the inside. The train stopped and the policemen asked questions and threatened to kill those inside the car. They did not notice the broken window but they noticed the open latch on the door and rewired it shut. Michael repeated the process, opening the door a second time from the outside. This time, Michael grabbed his father and pushed him out. A commotion in the wagon began as Michael tried to save others, eventually jumping off with his sister Bella and four others.

Michael recalled exiting the train: “But then, we’re outside. We’re looking at one another, we’re looking at the sky. And we’re looking at the ground, and what do we do now? Where do we go?” They did not know where they were when they exited the train but they had a calling to go back to Lida to find the partisans. It was a bright night and the stars were clear. They located the Big Dipper to determine north and south and used this knowledge to locate Lida. Michael had known about the partisans in the brewery which was part of the reason he had stayed there. They would come to the brewery for supplies and then go to the ghetto with yellow stars on in the morning.

Now 120 miles past Lida, Michael and the group who jumped from the train wandered in the woods for two weeks, helped along the way by a kind young peasant who directed them to a Russian partisan camp who were organizing resistance against the Nazis. They were advised against returning to Lida for risk of capture. The Russian partisans helped them get to a village in the Lipichanski forest which was a transfer area to the Bielski group located in the Naliboki forest. Here, Michael unexpectedly saw a Jewish friend from Lida and learned that his mother and sister were safe. They had hidden in the brewery attic with three other families, including his cousin Vivian, made a rope to climb down and escaped into the forest. A woman with two young children, they managed to find refuge with the all-Jewish Bielski partisan brigade, situated more than 75 miles from Lida. The Russian partisans then guided Michael, Bella, and Leon, to the Bielski partisan camp, where they were reunited with their family.

Michael and his family arrived deep in the Naliboki woods at the Bielski family camp in late 1943. Michael participated in missions where partisans were sent out to a village or town to bring back supplies and food for the camp. For example, one mission included going back to the brewery in Lida to dig up weapons Michael had hidden earlier. Contrary to the Russian partisans who were helpful, there were other Russian partisans who were unfriendly and one such group took Michael’s rifle, coat, and boots in the dead of winter on another mission because he was part of a Jewish partisan group. Regarding his courage to fight back as a partisan, Michael recalled: “I did not know… I never dreamed in my life that I’d have that kind of will to fight back. I didn’t know I had it in me, but life teaches you certain things”.

Michael stayed at the Bielski camp until July of 1944, when they were liberated by the Russians. His family returned to Lida, but most of the town had not survived or had disappeared. Only two families in Lida survived intact, including Michael’s.

The family once again returned to the brewery, where they worked until 1945. The family then decided to go to Leon’s hometown of Lodz, Poland. Still, due to complications with Polish citizenship, they left Poland and went first to Czechoslovakia and then to a series of Displaced Persons camps in Austria until 1949.

Although his first choice was to go to Palestine and fight for establishment of the State of Israel, Michael lost that battle with his mother so on August 13 of 1949, Michael left for the United States aboard the USS General Blatchford, arriving on August 22nd. Ironically, while he was unable to obtain a job because he was not yet a citizen, in 1950, he was drafted into the U.S. army during the Korean War and served in Indianapolis where he worked as an interpreter in Russian and German and also learned English during this time.

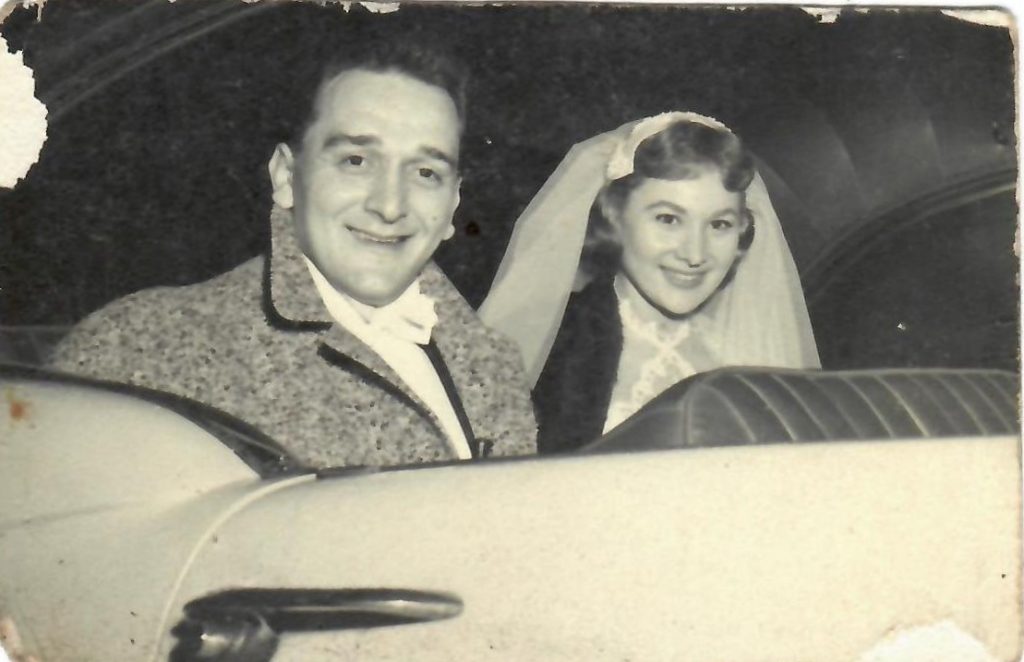

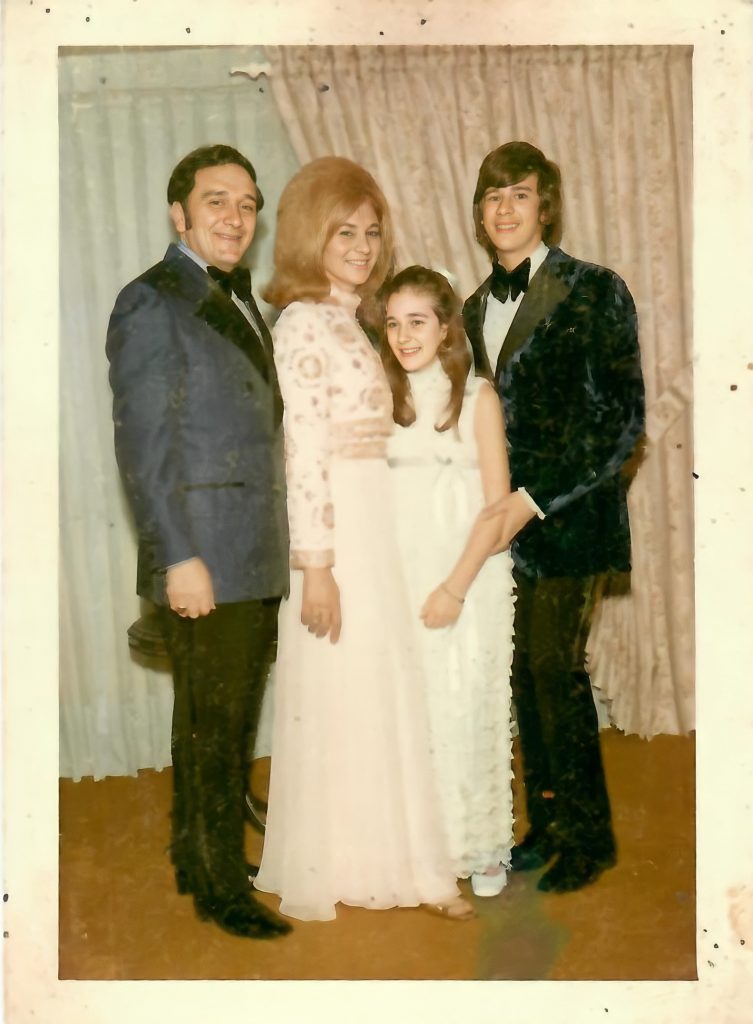

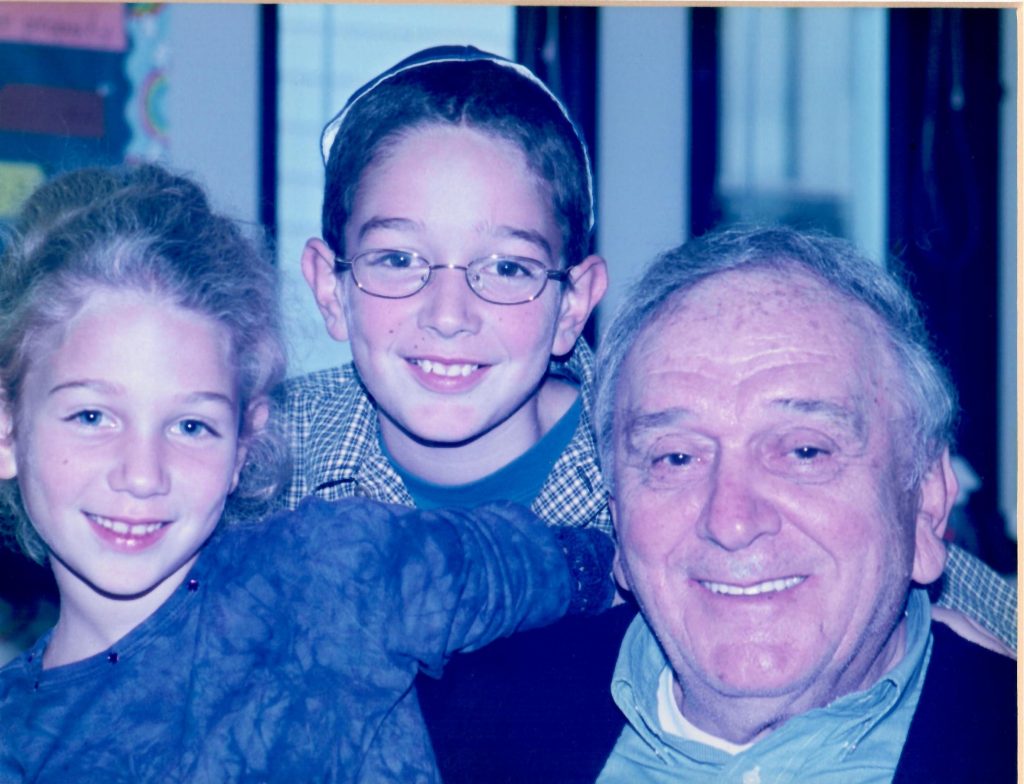

In the United States, Michael met his future wife Etta Greenblatt, who gave him the push to start his own business. Etta and Michael married in 1957 and had two children: Andrew and Nancy. Michael has two grandchildren, Ian and Suzanne, and lives in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Michael built a business as a manufacturer, wholesaler and retailer of decorative tables and mirrors in Brooklyn, NY, where he and Etta raised their family. They vacationed in the summer and winter in the Catskill Mountains of NY, where Michael taught his children to ski. He often took his children and nephews with him on ski trips to Colorado, Italy and Austria. After his retirement, Michael would spend a month every winter in Utah where he continued his love of skiing.

One of his most satisfying accomplishments was to see his son become a doctor.

Michael spent many years as president of the Lida Holocaust Memorial Foundation which aims to cherish the memories of all those who were lost in Lida and its neighboring communities as well as commemorate those who survived – with the hope of keeping the Lida spirit alive for generations to come. A memorial service is held every year close to the Yahrzeit of May 8, when most of the townspeople living in the ghetto were murdered in 1942.

In 1973, Michael traveled to Israel with a group of Bielski partisans and met with Golda Meir who offered her gratitude and a tribute to those who fought as partisans.

In 1994, Michael traveled back to Lida with his sister Bella, other surviving Bielski partisans, his wife and two children, and received a hero medal from the government of Belarus to acknowledge the 50th anniversary of the end of the war.

Over the ensuing years, Michael was interviewed on camera for films documenting his and the partisan experiences including, The Shoah Foundation, Jerusalem in the Woods, Defiance, The Train, and Four Winters. A book about his life is forthcoming once a publisher is secured. Over the years, Michael has spoken about his experiences to many groups of young and old at schools, colleges, synagogues, and community groups throughout the northeast United States and Canada.

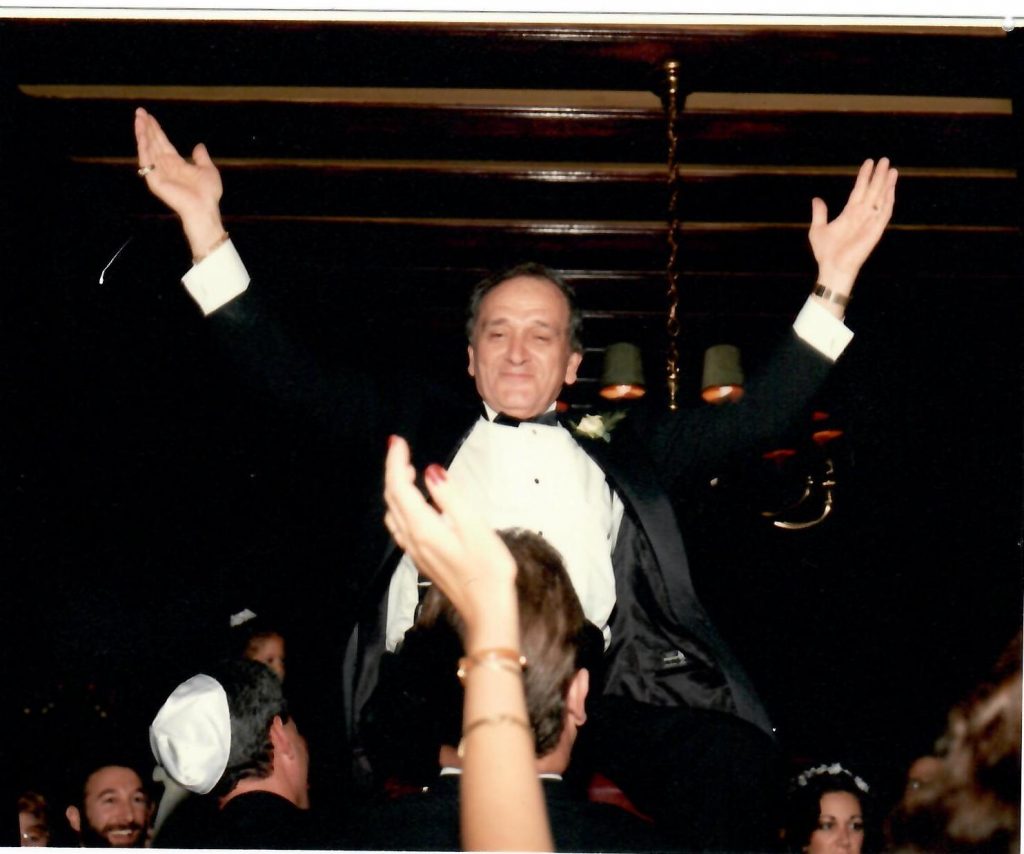

In 1997, Michael and Etta retired to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to be close to their grandchildren who were toddlers at the time. Etta passed away in 2000. Michael remains very close to Ian and Suzanne and had the good fortune to spend the entire COVID quarantine year living with them at their home in Lenox, where he moved in 2018. Michael is thrilled to have attended and danced at Ian’s wedding in July of 2021.