Morris Rosnow was born to Chaim Michel Rosnow and Chana Rashka Rosnow on January 7, 1927, in the town of Zhetl, Poland, today Diatlovo, Belarus. Morris, his two sisters, Mira Shelub and Sara Rosnow, and his father survived the war in the nearby woods with the help of the Bielski partisans. After the war, he was in a Displaced Person’s camp in a hotel near Salzburg, Austria, and later emigrated to the United States to start a new life before putting himself through pharmacy school and starting a family in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Morris’s hometown of Zhetl was a small but vibrant shtetl of 4,000 people, 3/4 of whom were Jews. The town had two synagogues, a market square where farmers could sell their goods, and local bus services to nearby Vilna, 80 miles north of Zhetl.

Morris fondly remembered his childhood before the war. Life for Morris was very simple, rural, and economically impoverished, but his family found ways to persevere. Morris recalled a special moment when his father brought him ice skates. He had been skating up to that point by placing a wire under his shoe. Late into life, his face would light up at the thought of those ice skates.

He attended the Yiddish Folkschool, which he loved. The school had rich programs on Yiddish culture, often putting on shows for the town. Morris’s father was on the board of the school.

On a typical day after school, Morris would spend the afternoon first going home to have supper with his grandmother, then spending time at his parent’s store or out playing with friends.

Life in Zhetl started to change with Soviet occupation under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact which divided Poland between the Soviets and the Nazis.

In his Shoah testimony, Morris recounts how Jews in his town found relief in the Soviet occupation, as a protection against the Nazi threat, the scope of which they did not yet fully understand. Nevertheless, life under the Soviets significantly changed. The Jewish schools were closed and replaced with Soviet education. Morris and his sisters were set back in their studies and were learning Russian rather than their native Yiddish. Morris saw these as generally happy times and spoke fondly of the activities for youth under the Soviets.

Soviet occupation made Chaim Michel’s store no longer viable. Not only was it difficult to buy goods to stock the shelves under Soviet rule, but the merchant class was no longer valued under communism. Morris recalls that when the Soviet forces moved through the town, they would buy whole shelves of goods at the store. This seemed like a windfall profit until they discovered there was no way to replace the goods under Soviet rule.

Eventually, the store would close and Chaim Michel would support the family by selling insurance in the town.

While things were stable under the Russians, Morris recalled that they sometimes would receive guests traveling eastward who had concerning stories about atrocities towards Jews by the Nazis. While these warnings were deeply scary, as Morris recalled in his testimony, “Even if we wanted to leave, we had nowhere to go”.

On June 22, 1941, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact ended with the German invasion of eastern Poland. Morris and the other Jews were all surprised by how quickly the Soviets fell to the advancing Nazi army. The mighty Soviet military presence seemed to be no protection after all.

On June 30, 1941, the Nazi SS created a presence in Zhetl and, under their control, a Judenrat was created and a ghetto was formed. Jews from other parts of the town were moved into Morris’s area and the family took in people to live with them in their already-small quarters. In the case of Zhetl, it is notable that the head of the Judenrat, Alter Dvoretsky, was also leading the town’s resistance. Dvoretsky heroically was killed while organizing an effort to free the ghetto.

On July 23, 1941, the Nazis called a meeting for town leaders. Morris’s father was on the list of those required to attend but he was in bed sick that day. Morris and Sarah asked a German soldier if he needed to attend anyway and, thankfully, that soldier told them that if he was sick, he should probably stay home. That single humane response meant that the family retained the leadership of their father through the war, and all agree they probably would not have survived without him.

No one who attended that meeting was seen again. They were all shot dead in a pit outside of town. When news of that massacre got back to the town, Jews started building hiding places so that they might evade another killing.

Morris’s family expanded the cellar below their house, built a hiding space in their attic, and built a hiding place by adding a false wall to their outdoor shed.

These hiding places were put into use on August 6, 1942, when all the Jews of the town were called to the town center. Morris and his family did not attend, instead using their hiding places. On that day, nearly all of the Jews of Zhetl were murdered by the Nazis.

From their hiding places, Morris’s family could hear the local gentiles looting the neighborhood and, in many cases, they heard the sound of Jews being found and turned in to the Nazis. Thankfully, none of their hiding places were discovered and they were able to wait until the lootings abated.

Eventually, the Nazis and the looters moved on and Morris and his family emerged from their hiding places.

As they emerged from hiding, there were a few days of tense confusion for the family because they could not locate his two sisters who had been hiding in the outdoor shed. When Morris and his parents went to look for them, they could not be found. It was not clear if they had survived or had been discovered.

Jews who survived the mass killing in the town were left without much sense of what to do next. With the life of the town destroyed, it was not clear how or if they could survive in Zhetl.

It was known that within walking distance of the nearby town of Dworetz, there was a work camp where one could receive rations by helping to build airfields for the German war effort. Morris and his parents traveled there, where they found his two sisters, safe and sound.

The family worked together at the camp until, one day, two men from the local woods came to recruit people to join the partisans in the woods. Mira and Sarah, not feeling safe under German authority, decided to leave with the recruiters. Morris was also interested but his parents did not want to leave the camp, so Morris stayed with them. Morris eventually convinced his parents to leave the camp and go find his sisters in the forest.

They were all united in a forest encampment that would eventually become part of the Bielski partisan group.

Morris and his parents made their way to the Bielski group and were part of the Bielski Family camp. Morris was not a member of the fighting group but did serve by keeping watch at night. Morris spoke about taking the armed watch as a very serious duty to protect the camp. He was also active in building the camp shelters (zimlankes).

Morris described how he would build zimlankes, first by digging out an area and covering it with branches and then covering the branches with dirt. The partisans could sleep inside and in some cases, they could keep a stove in the zimlanke for warmth.

Morris suffered terrible frostbite during the war that threatened to badly affect his feet. His mother gave his feet constant attention and after a very long time of rest, he made a full recovery.

Morris described the partisan encampments as relatively safe, however, they were attacked occasionally by Nazi raids.

It was on one of the raids that Morris’s mother, Chana Raska, was killed. Morris was able to run away and save himself. On his way back to the camp he found his mother’s shoe and had thought he could bring it back to her. Upon returning to the camp, he discovered his mother’s tragic fate.

Morris’s father was able to survive the war but was very sick by the end. While he made it to liberation by the Soviets, he died months later.

Morris’s sisters, Sara Rosnow and Mira Shelub, both had experiences with the Bielski fighting group which they recount in their own partisan histories.

After liberation in September of 1944, Morris left Poland and first traveled to Lodz, Poland, where he stayed with a youth Zionist organization, similar to a kibbutz, until the end of 1945. He then traveled to the Bad Gastein Displaced Person’s camp near Salzburg, Austria in the early months of 1946, where he joined Mira and her husband Norman. Sara joined in the later months of 1946. Sara and Morris also lived in Munich, Germany for two years, attending the Technical University (the Technische Hochschule), where Morris studied engineering.

Morris, his two sisters, Mira’s husband Norman, and their son Irwin were sponsored to enter the United States by family in Baltimore and Philadelphia, who emigrated before the war under the English name Raznov. Mira and Norman left for the United States in 1949. Morris and Sara immigrated the next year, in 1950. They left from Bremerhaven, Germany aboard the USS General Stuart Heintzelman in December 1949, arriving in New York in January 1950.

Morris stayed with Uncle Irwin, his father’s brother, and his younger cousins Ralph and Nancy in Baltimore, around the time of Ralph’s bar mitzvah. Ralph recalls a memory of sitting on the tub in their bathroom, watching Morris shave, and thinking that Morris was a real man.

Morris entered the United States with $200 he had earned on the black market selling cigarettes while in the Displaced Person’s camp. As he considered how to support himself in his new life, Morris observed his cousin Jack was doing well as a pharmacist and envisioned himself doing that type of work. Following his sisters who decided to start their new lives in California, Morris left for San Francisco in November of 1950.

Morris worked in a warehouse on the San Francisco docks where he saved money while living with his sister Mira and her growing family. Morris was able to save enough money to put himself through pharmacy school and UC Berkeley. After graduating in 1956, Morris was unable to obtain a job because the openings required a year of experience and he was unable to obtain any experience without a job. He found a pharmacy that would permit him to work for a year, without pay, to gain the necessary experience. He worked there for a year until he found a paying position.

The Temple Emanu-El synagogue in San Francisco held Jewish singles dances. One night, Gina Einstein, who also attended the dances, cut her long hair into a new, modern hairstyle. When Morris approached her to find out who the new, beautiful girl was, Gina responded that “It’s me, Morris, Gina!”. They decided to go out for coffee and the rest is family history.

Gina was also a new emigree. Born in Stuttgart Germany in 1932, her very astute mother saw the threat of the Nazi rise to power and moved the family to British Mandate Palestine for the duration of the war. Gina’s family later made their way to the United States and the San Francisco Bay Area. She attended UC Berkeley and San Jose State, and was starting a career in Occupational Therapy when she and Morris met.

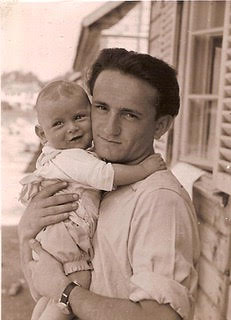

Morris and Gina pursued their love and married in 1962. Their first son, Harley Michael Rosnow, named after Morris’ late father Chaim Michel, was born in 1963, in Burlingame, California. Their daughter Heather Einstein Rosnow, named after Morris’ late mother Chana Raska, was born in 1966. Their third child, David Samuel Rosnow, was born in 1970. They have two grandchildren from Harley and his wife Yuriko Sugihara Rosnow, Kinori Sugihara Rosnow and Rina Sugihara Rosnow.

Morris and Gina established their own business, Clayton Valley Pharmacy, in the growing city of Concord, California. Clayton Valley Pharmacy thrived over the years, due in large part to Morris’s love of people. With his warm Yiddish-accented English, he treated each customer, delivery boy, and company representative as a person, not just a business connection. He knew all his customers’ names, their families, and their medicines, and watched out for any dangerous interactions from their prescriptions.

Morris and Gina were also founding members of Congregation Bnai Shalom, where Morris was a member of the religious committee for many years. He gave talks in the greater San Francisco Bay Area community on Holocaust education. The most important thing to Morris was to create a safe life for his family so that they never experienced the hunger he had in the war. He passed on these values to his children.

In 1972, the family moved to Walnut Creek California, where Morris lived until his death in 2015 and where Gina lives to this day.