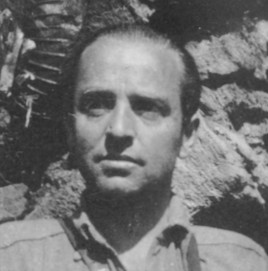

Moshe Berkowitz was born in 1898 in the small Jewish town of Woronowa, Poland, now in modern-day Belarus. Residents of Woronowa shared a strong religious faith and admiration of God’s teachings; Jewish rituals were deeply woven into their society. During this period, Jews in Woronowa were unaware of their imminent destruction.

On June 22, 1941, the sound of exploding bombs woke the residents of Woronowa. German planes had thrown bombs and distributed leaflets containing Nazi propaganda. With insufficient preparation time and no defense, life in Woronowa began to decline. Nazis marched into the town the following day and murdered several Jews. Moreover, the Nazis burned books and destroyed written records. Eventually, the Nazis established a police force to monitor the activity of Jews. They forced the Jews into hard labor and to obey strict orders. Struck with a sense of hopelessness, residents of Woronowa felt that they had to surrender to their destiny.

One morning, the German police broke into Moshe’s house and accused him of not fulfilling a job assignment. However, there had been a misunderstanding, and the police forgot to cross his name off the list for that job. After being whipped by the Germans, Moshe, and other Jewish men were driven to a local prison and forced into a small prison cell. The men were later lined up to be executed, but luckily the soldiers sent them back to prison before they could be shot. After spending two days in prison, Moshe and the other men were released.

A month after the Nazi occupation of Woronowa, a Judenrat (Jewish Council) was established, which helped the Nazis organize a workforce, enforce taxes, and collect materials for their war effort. The Nazis demanded a tax on grain from Jews, so food was in short supply. The Jews were ordered to gather in the marketplace to work, and those who did not fulfill this requirement were killed. There were frequent raids of Jewish homes by Gentile police in the middle of the night, which was the local Gentiles’ idea of amusement. Some Jews paid large sums of money to the Nazis in an attempt to ensure their safety.

One day, a Gentile messenger informed the Woronowa Jews that Lithuanian Jews were being massacred in nearby towns. More than 500 Lithuanian Jews sought refuge in Woronowa and shared their last morsels of food with the refugees upon their arrival. On November 6, 1941, local police surrounded the town. The Gentiles released a barrage of gunfire and broke into Jewish homes. They shot at every fleeing Jew, but fortunately for Moshe and his family, the Gentiles had poor aim. They fled through the fields of Woronowa after hearing the gunfire, not knowing where to go or what was to come.

Moshe and his brother-in-law Reuben decided to escape to the house of a peasant they knew in hopes of finding shelter and protection. After Moshe and Reuben explained what had happened in Woronowa, the peasant vanished, and his wife demanded they leave immediately. They decided to remain in their barn despite threats that they would be reported to the authorities. Moshe and Reuben soon learned that the peasant had gone to Woronowa. When he returned, he explained that the raid was only aimed toward Lithuanian Jews and, therefore, the Woronowa Jews were not targeted. Nevertheless, Moshe and Reuben left the barn because the peasant ordered them to vacate his premises.

On their way back to Woronowa, Moshe and Reuben passed by the homes of Gentiles. They spotted armed German soldiers approaching at one point, so they hid in a grain field until the soldiers left. Then, after going unnoticed by the soldiers, they carefully crossed train tracks and made their way into Woronowa again. The deadly silence and darkness in the town filled Moshe with a sense of sadness. He and Reuben spent that night in the home of a Gentile, who they confided in until they were sure it was safe to return to their home in Woronowa.

When Moshe returned home, he became aware of the atrocities committed against Lithuanian Jews. First, he learned that the Nazis imprisoned 280 Lithuanian Jews in a cinema, where they were harassed and stripped of their belongings. Then, on November 14, 1941, the Nazis ordered the Lithuanian Jews to embark on their death march. Most of them were murdered and buried in a mass grave.

Roughly one month after the massacre of the Lithuanian Jews, the Nazis issued a decree that they would kill Jews who were old and sick to protect the population from disease. However, locals escalated the decree so that they were able to kill a more significant number of Jews. At the time, Moshe had a work permit given to him by the Nazis. As a foreman and mechanic, Moshe worked to repair radios and telephones and was respected by Gentile neighbors. Although the permit provided him special privileges to leave his house, he did not usually use these privileges because he feared harm if he left his house. However, on the day the decree was issued, Moshe left home and saw Gestapo men running in the street. The Germans ran from house to house to kill Jews, even young and healthy ones, as long as the Jews didn’t have their permits readily available. A total of 35 Jews were murdered that day.

Moshe began working on an estate with a few other Jews, one of them Chaim Dubliansky. Chaim wanted to set the estate on fire because the Judenrat refused to provide work for him, but the other Jews stopped him, fearful of the potential consequences. However, Chaim urged the others to defend themselves from the Nazis by forming a partisan group. He offered to supply them with firearms and ensured that they would manage to kill every Gentile who did not support them. Moshe and the others opposed this idea because they had no faith in its success and were aware of the severe consequences they would face if the Germans found out. In hindsight, Moshe regretted disregarding Chaim’s call for resistance. Soon after, Chaim beat Nazis that demanded his gold watch. He was sent to sent to jail and committed suicide.

As time progressed, Moshe and other Jews living in Woronowa began to hear rumors of Jewish partisans residing in the forests. For Moshe, deciding whether he and his family would escape to the forest was agonizing. The thought of heroic partisans filled his heart with hope, but he still could not imagine surviving in the woods. At this time, however, he was unaware that his town’s annihilation was inching closer.

On May 8, 1942, SS guards surrounded Woronowa. They ordered all Jews to remain in their homes, but Moshe’s work permit enabled him to leave. A guard told Moshe that the SS would strictly check Jewish documents to determine if any Jews were suspected runaway spies. The Judenrat told other Jews that only the sick and the old would be killed, which brought them great relief. Unaware of the lies being fed to them, they accepted this news without giving it much thought.

On May 11, Moshe and his family awoke to the sight of trucks carrying SS men racing through the town. Jews were driven to the marketplace and lined up by police. After Moshe’s family arrived at the market, his twelve-year-old son, Eliezer (Lazar), ran away and lied to the Nazis he encountered by saying he was a Pole. Unconvinced, the Nazis returned Eliezer to the marketplace.

The Nazis ordered 2,700 Jews to sit still in the marketplace; even small movements were punishable by death. They herded groups of Jews to their place of execution and beat them along the way. When Moshe and his family were about to be taken, Moshe’s boss pleaded with the Nazis not to kill Moshe. He was greatly needed by both his boss and the residents of Woronowa because he was the chief mechanic of the town. As he heard the resounding gunshots fired at his Jewish brothers and sisters, Moshe knew how fortunate he was to be saved from his execution. Unfortunately, 1,885 Jews were killed that day, and peasants and Gentile neighbors took their possessions.

Roughly 1,200 Jews remained in Woronowa. The chief of staff of the nearby town of Lida gave the remaining Jews a speech demanding their obedience and that they work for the benefit of the German people. The Jews were then ordered to march to the Bastuni station, where they were sent by train to Lida. They were crowded into dirty train cars with roughly 120 people in each vehicle. Upon arriving, the Jews were brought to the Lida ghetto. The conditions in the ghetto were challenging; they were crammed into small rooms, had limited food, and were assigned to strenuous labor. During the two months Moshe and his family spent in Lida; they dug an underground bunker they would later use as a hiding spot.

On September 17, 1943, Woronowa refugees living in Lida were taken to the Majdanek death camp to be gassed. Moshe, his family, including his wife Rasha and son Lazar, and his neighbors hid in the bunker they dug for six days without food or water as the other Jews were taken. One night, they decided to leave the bunker in hopes of escaping. Soldiers spotted them as they climbed over a barbed wire. The soldiers shot at them, but all of the bullets misfired. Moshe’s family was separated in darkness, and only two of his children remained with him. Although he and Rasha only had one child of their own, they looked after several other children who were orphans.

Cold and starving, Moshe and the two children managed to reach the house of a peasant they knew. The peasant gave them food but then ordered them to leave. At this point, Moshe felt that joining the partisans was their last resort, so they soon went into the forest and walked for six days looking for partisans. After reuniting with Rasha and two other children who had been separated, they continued to walk through the forest until they found a partisan group of 1,200 Jews.

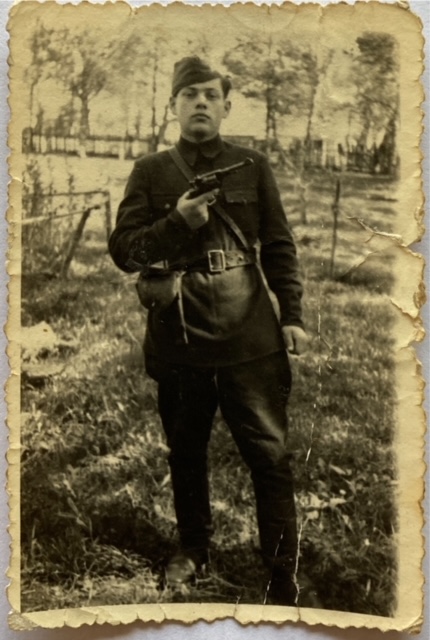

Moshe and his family lived with the Bielski partisan group for ten months. Often hungry, they lived in underground zemlyankas with forty people in each. Life in the forest consisted of constant fear of German attacks. The Germans built a powerful army that had access to advanced weapons and was dispersed across a large area around the partisans. The army wiped out village after village to cut off the partisans’ food supply and communication. The partisans’ base was heavily guarded on all sides and always stayed vigilant for enemies. Moshe and six other men were assigned to a post where a commander instructed them. The men often went on two-day-long walks to ensure that the camp was far enough from death camps. On one occasion, when Moshe was marching through the forest, he came across Russian riders who supplied him with food.

Despite their fears, the partisans remained hopeful. The Allies left leaflets in the forest, urging the partisans to keep fighting because victory was near. Then, one day, nine of the Jewish partisans died from a German attack. A few days later, the remaining Jews were liberated by Russians. Moshe survived, but many of the partisans in his group did not.

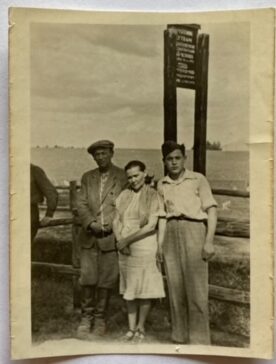

Soon after, Moshe and his family returned to Woronowa but had no place to go because Gentiles occupied his home. Other Jews soon arrived and managed to live in the town for another year. Moshe and his family then went to Poland, hoping to go to Palestine eventually, but he remained in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Austria and later Germany.

In 1948, Moshe, Rasha, and Lazar immigrated to the United States and moved to Boston. Moshe worked in a factory and wrote articles for the Yiddish language newspaper The Foward. Lazar, a young man when they arrived in the country, enlisted in the United States Armed Forces. Moshe passed away in 1961, and sadly, Lazar passed away in 1970, but Rasha lived a long life until 1986. Moshe and Rasha had three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren who today continue to tell their family’s story of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust.

This biography was written by JPEF’s student intern, Alex Boyarski, great-grandson of Jewish partisan Gertrude Boyarski (z”l).