Murray Gordon was born in pre-World War II Lithuania in the seaside resort town of Klaipeda. At the age of six, Murray and his family moved to Kovno, the capital of Lithuania, to be closer to his mother’s parents and siblings. Two rivers surrounded Kovno and this is where Murray and his brother ice skated in the winter and fished during the summer.

In 1940, the Soviets occupied Lithuania. Although the Soviets did not care much about the Jews, the Jews felt much safer under their jurisdiction than under Hitler’s fascist dictatorship. They knew that things were very difficult for Germany’s Jews. They also believed that Germany would never attack the Soviets, especially with the non-aggression treaty in place. Then on June 21, 1941, the Germans plunged forward and attacked the Russian Frontier, breaking the non-aggression treaty, successfully invading Lithuania, and pushing the Soviet Army back towards Russia.

Murray was fifteen years old, and his brother just eleven, when the Nazis began their occupation of Lithuania. They made decrees and put harsh restrictions on the Jewish people. During the first week, Lithuanian collaborators started rounding up all the Jews on the street and executing them right outside of Murray’s town. Then, in August, the Nazis told the inhabitants that they had to move to a ghetto ten miles outside of Kovno. The people hurriedly packed their bags, and were forced to carry all of their belongings with them as they walked ten miles by foot. There was a hospital inside the ghetto when they arrived, but as they stood in the field, the SS burned it down with 80 people inside, including nurses, patients, and doctors.

Just two months later, the inhabitants were told to go to the fields. The Nazis formed two groups of people – those who were able to work and those who weren’t. If they weren’t able to work, they were brought to a “resort area” where they were killed. Murray’s grandparents, two uncles and their families were among the 80,000 people killed. Murray, his father, mother and younger brother were left to work alongside the remainder of the ghetto population.

Murray quickly found out that there was an underground group working in the ghetto that had contacts with partisans in the forest. He worked with the underground for two years, sabotaging and derailing supply trains, blowing up bridges, and gathering intelligence. His perfect command of the German, Russian and Lithuanian languages was a tremendous asset. He was able to go back and forth between the forest encampment and the ghetto to visit his family.

On a mission to blow up an ammunition train, the German soldiers were able to escape harm, leading to a shootout between the five soldiers and the seven partisans. Sadly, all of Murray’s comrades were shot and killed. Wounded and lying on the ground, he pretended to be dead and when the sole surviving German soldier approached, Murray pulled out a revolver he had hidden under his coat and shot him. Murray made it back to the ghetto where he received medical attention for his five bullet wounds, but he could not leave again.

When the ghetto was liquidated during the summer of 1944, Murray and his father were separated from his mother and younger brother and sent to Dachau. In April 1945, just prior to the liberation of Dachau by the Allied forces, the SS forced 7,000 prisoners on a six-day-long death march to Tegernsee. Murray was among them. Along the way, those unable to maintain a steady marching pace were shot, while many others died from starvation or physical exhaustion. One night, Murray lay down to sleep, never expecting to awaken. Hearing the sound of voices, he woke to find that Allied forces had liberated the group and the SS had fled. Murray weighed only 98 pounds, but the feeling of freedom was beautiful. At one moment, Murray was facing death, and in a blink of an eye, he was facing the certainty of life, literally night and day – death to life.

Murray was reunited with his father, but sadly his younger brother was murdered in Auschwitz, and his mother died just two days before liberation. After the war Murray enrolled in Munich University and studied to become an electronic engineer.

Eventually, his Uncle Irving was able to obtain visas to bring Murray, his father and stepmother to the United States. Murray lived with his uncle in New York, working for CBS Columbia during the day and studying physics and business administration at night. His uncle gave him sound advice that he has followed throughout his life – “Invest in real estate – it makes money while you sleep”.

Relocating to the Bay Area, Murray met his wife Janet at a family dinner party and they were married in 1951. Following his uncle’s advice, Murray became a successful real estate developer in the East Bay, developing approximately 400 residential housing units. He also became President of C Markus Hardware, the largest hardware store in Oakland, California, which had been founded by his father in law.

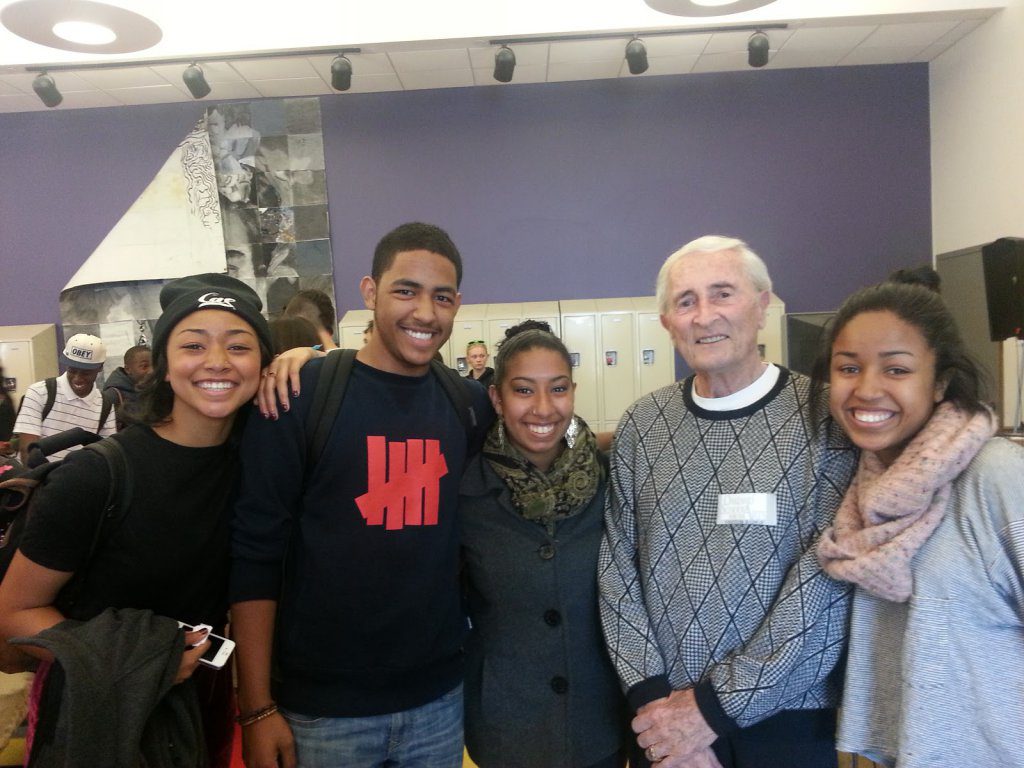

Married for 66 years, Janet and Murray raised three daughters and today they find joy in their six grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. Upon becoming a grandfather, Murray realized how important it was to share his experiences during the Holocaust, and his story of survival with others. Today, Murray continues to advocate for Holocaust remembrance and against discrimination in all its forms. For ma many years Murray spoke to school children and community groups throughout the Bay Area – making certain that the world never forgets. Murray passed away on July 6, 2020, surrounded by his entire family.

After first learning from Murray Gordon that there were Jews who fought back against the Nazis and their collaborators as partisans, Mitch Braff, JPEF’s Founding Director, was inspired to start the organization in 2000.