Murray (Motke Shmulewicz) Berger lived in a shetl named Wseilub in what was then Belorussia, White Russia. Wseilub was a small Jewish community with approximately 100 families. Murray was the youngest of seven children. All of his brothers and sisters were married and had children. Prior to the war, Murray was a rabbinical student studying at the famous Mir Yeshiva in Vilna.

After the Nazis first captured Wseilub they seized Murray and his brother Zemach and tied them to a tree. They were held as hostages. The townspeople were told that the two would be shot unless a ransom was paid. Luckily, a female doctor paid the money.

On Christmas Day, 1940, Murray saw the Commandant of the Police, Schultz, coming towards his home. Murray knew he was going to be arrested and taken to a labor camp. He hid in one room as the soldiers entered another and then jumped out of the back window and ran until he reached a field, hoping to find a place to hide. For over a year, Murray dragged himself through fields and back alleys to avoid detection. Desperate for food and shelter, he sometimes knocked on the doors of homes owned by gentile farmers. Thankfully, these righteous gentiles hid him in return for labor, but he could never stay in one place for too long for fear of being captured or bringing repercussions upon his benefactors.

On December 8, 1941, while hiding in a nearby forest, Murray heard the sounds of machine guns murdering over 4,000 Jews from the Novogrudok ghetto. By this time, more than 130 of his relatives had been murdered. Murray learned that the only surviving Jews were in what was left of the ghetto. He realized that his only chance of survival was to be with other Jews. He secretly latched onto a slave labor gang and sneaked into the ghetto.

The conditions in the Novogrudok ghetto, a slave labor ghetto, were horrendous. In the summer of 1942, Murray sensed that another massacre was soon to take place and was determined to escape. As he wrote, “If death had to come, let the bullet come from behind.” In other words, the end would come while he was escaping rather than submitting. He and others wanted to join the partisans and fight the Nazis. They wanted to do this despite the fact that there was tremendous antisemitism among the Russian and Polish partisans. Many of them would readily kill a Jewish fighter for a good pair of boots. But then he learned of a letter written by Tuvia Bielski that had been smuggled into the ghetto. It stated that Tuvia and his brothers were forming a Jewish partisan unit.

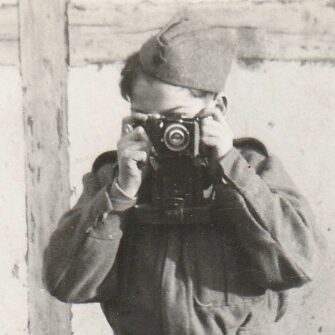

Murray was among the first seven men to escape from the Novogrudok ghetto and join the Bielskis. Another eight followed soon thereafter. Those fifteen men elected Tuvia Bielski to be their commander. Murray became a fighter in the brigade. He and the other fighters engaged in acts of sabotage, blowing up bridges and rail lines, destroying telephone lines, bombing Nazi police headquarters, and, at times, engaging in open combat.

“Our salvation lay in revenge…Revenge in the name of my family and for all the Jews…The purpose was to harm the enemy every step of the way. As quickly as we received weaponry, we made good use of it.” And, very importantly, Murray, along with other members of the Bielski Brigade, rescued other Jews. The Bielski Brigade grew into a forest community of more than 1200 Jews.

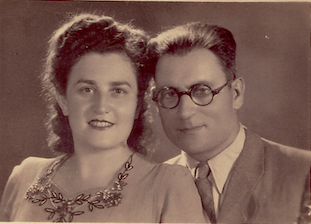

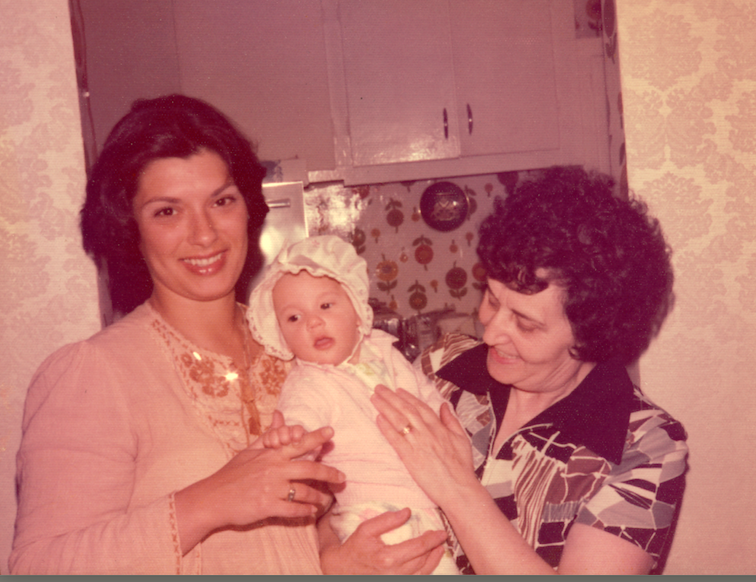

In the brigade, Murray met his future wife, fellow fighter Fruma Gulkowich (Frances Berger). In later years he would smile slyly and tell people, “I found my wife in the woods.” Following liberation in the summer of 1944, Murray and Frances, along with Murray’s brother Ellie, and Frances’ brother Ben-Zion and his wife Judy, crossed war-torn Europe and lived in Displaced Persons camps for two years. Murray and Frances were married at the Great Synagogue in Rome in 1947. They emigrated to the United States later that year. They became proud citizens, raised two sons, Albert and Ralph, and in later years, took great delight in spoiling their grandchildren, Beth and Brian. After working primarily in construction, Murray learned a trade and, like his brother Ellie, became a printer for the Forward.

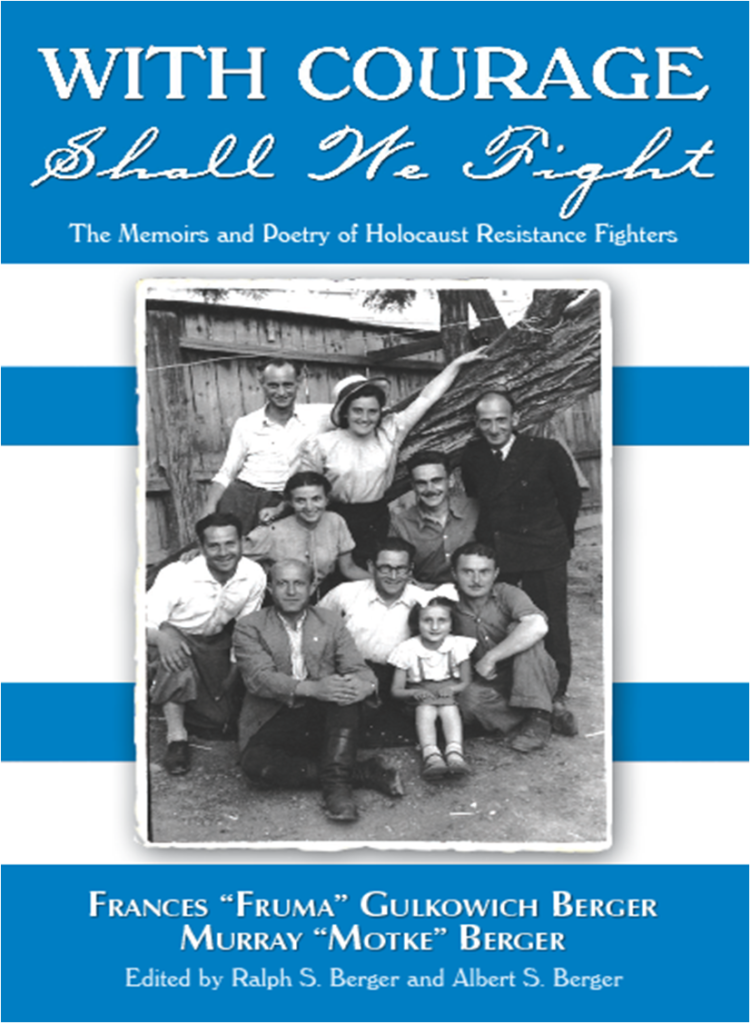

Both Murray and Frances never stopped engaging in Holocaust education. They wanted the world to know that Jews did not go like sheep to the slaughter and that when they could, Jews fought back, physically and spiritually. They wrote articles and gave interviews. They lectured to students. The book With Courage Shall We Fight: The Memoirs and Poetry of Holocaust Resistance Fighters Frances “Fruma” Gulkowich Berger and Murray “Motke” Berger (Comteq Publishing, 2010) is a compilation of Frances’ and Murray’s writings and Frances’ poetry, as well as a pictorial history. It tells about their lives before, during, and after the War.