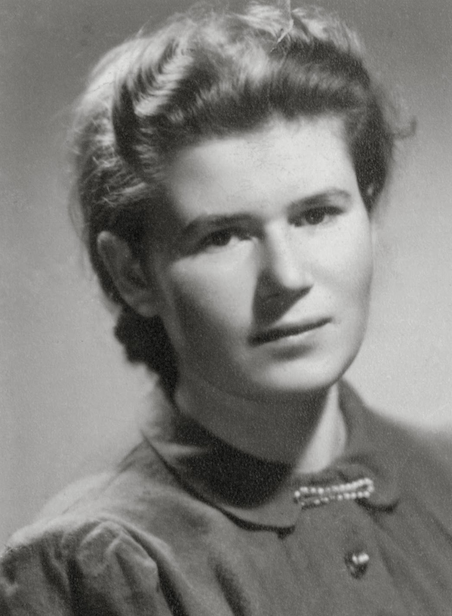

The eldest of two daughters, Sima Simieticka was born on March 8th, 1923 to a family of tailors in Warsaw. Her father left the family for Russia when she was only two years old – going to the newly-established Soviet state to seek his fortunes but instead ended up in front of the firing squad for being a Trotskyist. Sima and her sister lived with their mother and grandfather, who both worked as tailors, often accepting bartered goods in payment for their services. The family was very poor and often went hungry.

Despite these difficulties, Sima attended school until the age of 14. Two years later, in autumn of 1939, the Nazis invaded Poland and the family fled across the Bug river to Soviet-occupied territory. Unfortunately, Sima’s grandfather stayed behind. Sima and her family ended up on a work farm, where they remained for a time, doing whatever work needed to be done. Though life under the Soviets was difficult and fraught with hidden dangers1, Sima and her family persevered.

At one of the camps, she was forced to work on a farm located outside of the camp premises. Compared to the camp, she was treated nicely there and even received extra bread rations, which she was careful to share with her mother and sister (by walking as fast as possible so she wouldn’t have time to eat it all). When a rumor spread that her labor camp was about to be burned, she found a hiding place underneath an oven in a local hospital. She remained there for three days with ten other people, hiding in silence. Unfortunately, her mother and sister were not allowed inside the hiding place as there was not enough room or air for them. They were both gassed and then burned in the ovens.

After ten days of hiding in the cramped space, Sima decided she would rather be shot by a guard than burned alive or suffocated, so she left her hiding place. She vividly remembered her escape, how she took off her wooden shoes and crawled underneath the barbed wire. The camp was burning; it appeared that no guards remained on the premises, but she heard music coming from a watchtower, so she knew to be wary. In the bitter cold of the midwinter night, she ran to the house of the farmer she worked for. His dog recognized her and started barking, but she called out its name – “Lizek, be quiet!”

She was lucky: the farmer was friendly, and prepared a bed for her. Early the next morning, he woke her up, gave her a big breakfast, and told her where the partisans were. For one week she walked through the deep snow and across frozen rivers – only to be turned down for being Jewish by the first brigade she came across. She did better with the next brigade – a group of about 15, which allowed her to join. The brigade accommodated Russian soldiers, some Belarussian civilians, and even a German deserter. Though she was a Jew and a woman, she was accepted because she was one of the first and worked as a nurse. She was even issued a weapon, although she never had occasion to use it, and could have easily been robbed of it by antisemitic partisans who took to harassing other Jews in the otriad. And as a young woman trying to survive on her own in the forest, she was constantly under threat from the men she lived with. “You defend yourself as long as you can. If you cannot anymore, you stop defending yourself,” Sima stated grimly.

The otriad focused on survival; when they were not on the move, they spent much of their time hiding in zemlyankas – holes in the ground covered with branches, where about 4-10 people could stand upright. They gathered food by taking supplies from peasants, and by foraging for berries and other edible growth.

The Soviet parachutists landed in the spring of 1944, bringing with them guns and liberation. Free to go wherever she wanted, she chose Lodz, arriving there on the back of a truck, uninjured and in good health. In Lodz, she was able to locate her cousins with the aid of the Joint Distribution Committee. They had returned there as well, after surviving the deportations to Siberia.

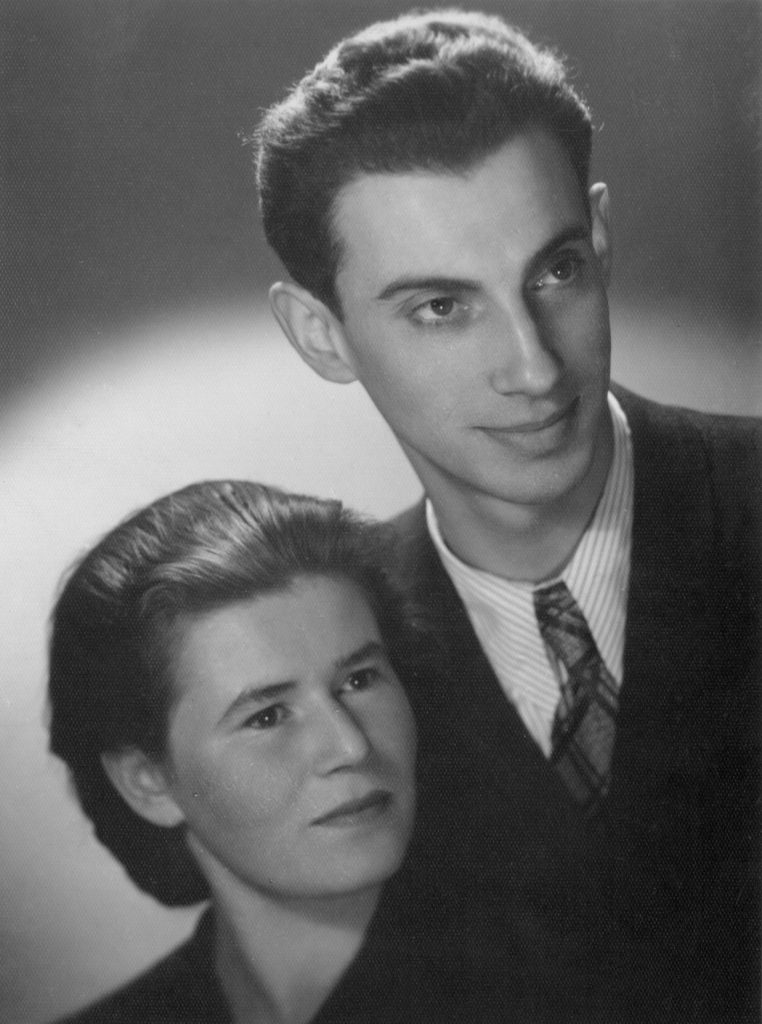

There Sima met her husband Stanley and together they immigrated to Germany. Though Sima received an offer and the necessary immigration papers from her uncle to join him in Brazil, Sima’s husband refused to leave Germany and give up his career in medicine to become a tailor in a foreign land. Consequently, they remained in Germany for the rest of their lives.

1. On one occasion, the local Soviet administration asked all the refugees where they eventually wanted to end up. Nothing happened to those who said “Russia”, but anyone who said “Poland” or “Warsaw” was deported to Siberia. Some of Sima’s cousins were deported there in this fashion.