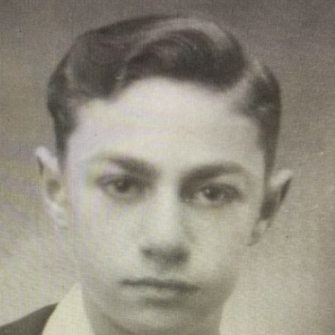

Srulik Porter (Yisroel Puchtik) was born on March 15, 1906 in the quiet shtetl of Horodok, Ukraine. He lived with his parents, Yankel and Esther Yentel, along with eight brothers and sisters: Chaim Moshe (Morris), Levi Yitzchok (Leon), Michla, Rochel, Velvel, Chasya, Zelda, and Baruch Leib (Boris). Srulik was drafted into the Polish Cavalry in 1923, where he became an expert horseman.

In 1937, Srulik Porter married Faige Merin, born in Horodok, Ukraine, in 1909. Srulik and Faige were soon blessed with a baby girl, Chaya Yudell. Two years later their second daughter, Pessel, was born. Very soon, however, their simple shtetl life came to a terrifying end. In 1939, the German Army invaded Poland. As the Polish Army retreated, they passed through Horodok, where they encountered Russian troops. The clashing armies resulted in Horodok going up in flames. It was Erev Yom Kippur, and the Jews ran into the forest to save their lives, leaving the food that they had prepared to eat before the fast on their tables.

Faige, Srulik, and their family relocated to the nearby shtetl of Manyevitch, which the Nazis later took over in 1941. The Nazis stole the population’s gold, silver, and furs, giving the local Ukrainians permission to rob the Jews. Every Jew had to wear a yellow Star of David on their clothes, and food became scarce. Srulik and other Jewish men were forced to do manual labor for the Germans. “Herr Commandant, will a good Jew, a good worker, be allowed to live?” Srulik asked a German guard one day. The German replied with a sadistic smirk, “Oh yes, the best Jew and best worker will be the last Jew.” Srulik understood from this conversation that the Nazis would kill all of the Jews in the end, no matter how hard they worked.

In the late summer of 1941, the Einsatzgruppen marched into Manyevitch. They rounded up the able-bodied Jewish men, heads of households, and Jewish leaders of the community and took them away in trucks to a large pit outside of town. They were cruelly beaten, stripped naked, and shot into the pit. In one day, 375 Jewish fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons, were killed in an area called the “The Horses Grave.” Srulik and Faige’s brothers and brothers-in-law were killed as well as Srulik’s father.

Srulik managed to escape the first round-up by the Nazis miraculously. On September 2, 1942, the Jews of Manyevitch were enclosed in a ghetto and surrounded by guards. Srulik knew that he must do something drastic. He kissed his wife and two young daughters goodbye and sneaked out of the ghetto disguised as a Russian peasant to join the partisans. Srulik hid for a few days until it was safe to contact his friends. He obtained a rifle, 150 bullets, 2 hand grenades and was told where to find a partisan group in the forest.

Srulik joined the Kruk-Max Otryad, a partisan group that began with only fifty men and two rifles. When Srulik came to the group with weapons and ammunition, the partisans were so happy that they kissed the rifle. Within three months, their group grew to 200 fighters consisting of 180 Jews and 20 Russians/Ukrainians. In addition to the fighting group, there was a group of civilians: older men, women, and children.

The partisans’ mission was to slow down Nazi supply lines and sabotage their operations under the cover of darkness. They placed bombs on Nazi railroad tracks and police stations to disrupt communications. They blew up bridges, water installations, and took revenge on Ukrainian collaborators, police, public officials, and Ukrainian Nationalists who worked with the Nazis. Srulik was later awarded the medal “Partisans of the Patriotic War–First Class” by the Russian Army for the many missions he completed.

In the winter of 1942 and 1943, the Nazis discovered and burned the partisans’ encampment in the forest. The partisans and civilians fled through the swampy, dense forest until they found a location to set up a new camp. In addition to keeping watch for Germans, there were Russian partisans who were anti-Semitic. One day, Srulik and his fellow partisans were informed that their camp would be attacked by one such partisan. They doubled the guards around camp, and everyone stayed on high alert for two nights until the danger passed.

The partisans received word that the Einsatzgruppen had murdered the Jews of Manyevitch on the 23rd of Elul 1942. Srulik was devastated as he thought of his elderly parents, dear wife, and two sweet, innocent young daughters. Now more than ever, he was determined to take revenge for what the Nazis had done to his family. Months passed before he heard that a cousin had survived. With trepidation and hope, Srulik made his way back to Manyevitch. Instead of finding a tall man, he found a small woman–Faige! She weighed only eighty pounds as Srulik carried her back to his unit. After Srulik nursed her back to health, Faige became a cook and nurse for the partisans.

As time went on, the partisan group broke into two groups: the fighters and civilians. The Russian commander thought the family camp was becoming a burden for the fighters as now hundreds of people needed to be fed and protected. The partisans were the ones who went into the villages to get the food and supplies needed. The commander decided to sever ties with the family camp and move to a different location. Srulik knew that these young children, women, and older men would not survive independently without the protection and food the partisans provided. Srulik asked the commander to allow two other partisans to help him, and they would take over the family camp. The commander agreed, and Srulik was given the responsibility of feeding and caring for hundreds of people’s needs.

After two years of living and fighting in the forest, they were liberated by the Russian Army in 1944. But where could they go? Srulik and Faige had lost their entire family. There was no one left alive in Manyevitch or Horodok. They did not even have a picture of their daughters. They traveled to the nearby city of Rovno, where they settled in a small apartment that they shared with other families.

Faige became pregnant while the Nazis were bombing Rovno. When Faige was ready to give birth, the only place they could go was to a bombed-out hospital. There was no heat or light as she delivered a healthy baby boy on December 2, 1944. They named their son Yankele Nusson (Jack Nusan) after Srulik’s father, Yankel, and Faige’s father, Nusson.

During this time, Srulik worked with other survivors in a Russian shoe factory in Rovno. Srulik knew they would not survive on the meager wages the Soviets were paying, and so they sold the left-over leather on the black market. With the fear of Srulik being drafted into the Russian Army and the NKVD on their trail, Srulik, Faige, and baby Yankele sneaked out of Russia. They obtained false papers from Breicha, an underground Jewish Agency, which stated that they were with a group of Jewish Greek citizens caught in Russia during the war who were trying to return home.

They traveled to the Bindermichl Displaced Persons camp in Austria near the city of Linz. They planned to go to Israel next, but Faige was not well; the malnutrition, living outside in the forest through two winters, and the unbearable losses had taken their toll on her. The doctor at the camp told Srulik that the extreme heat in Israel would be difficult for Faige to withstand, as she also had a weakened heart. After eight months in Bindermichl, Srulik, Faige, and Yankele immigrated to America to be with Srulik’s only surviving brother, Morris. They traveled on the SS Marine Perch and arrived in New York in July 1946 before reuniting with Morris in Chicago.

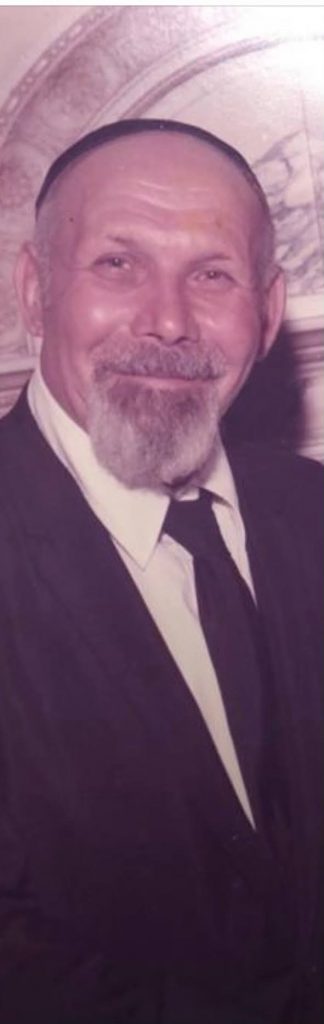

Srulik, Faige, and Yankele later relocated to Milwaukee, where they had extended relatives. Srulik started a scrap metal business and was a hardworking, diligent worker. They had two more children, Shlomo (Solomon) on November 9, 1947, and Bella Yenta on November 7, 1953. Srulik and Faige were generous people who felt strongly about giving people in need a place to stay. They opened their home to countless people throughout the years, and there were always Shabbos guests around their table.

Srulik was a warm, friendly, gregarious man with a twinkle in his eye who made friends with anyone he met. He openly shared his experiences of the war, passing on the lessons of the Holocaust to his listeners. Srulik passed away from cancer at age 73 on March 19, 1979. He was a strong, resilient partisan who was loved and respected by all who knew him.

![IMG_20210201_145803[1] IMG_20210201_145803[1]](https://www.jewishpartisancommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/IMG_20210201_1458031-1.jpg)