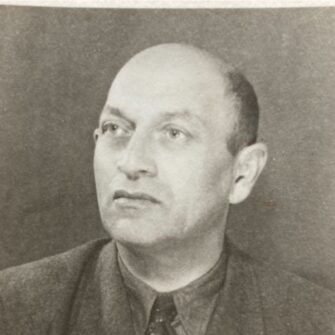

Ted Winestone was born Moshe Tuvia Wajnsztejn on September 24, 1929, in the small town of Baranowicze, Poland, now the Republic of Belarus. He lived with his parents, Rivka (Zaczepinski) and David, along with his younger brother, Noach, and grew up among his many aunts, uncles, and cousins. Antisemitism was prevalent in Baranowicze, a town of 30,000, with more than one-third of the population Jewish. Tuvia learned to stay away from certain areas in town where attacks by antisemites were rampant.

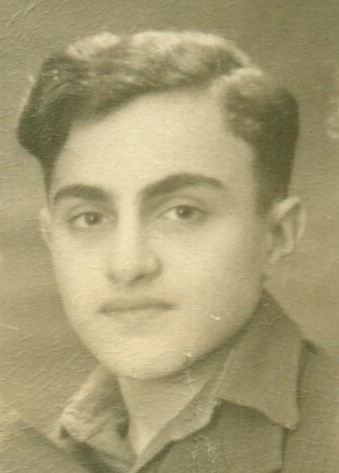

In 1939, Germany and Russia signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which divided Poland between the two counties. Under Russian control, Tuvia’s father lost his textile business where he had been a co-owner. Tuvia attended a Russian school and was forbidden to study Hebrew.

On June 22, 1941, Germany broke the non-aggression pact with Russia and invaded the Soviet Union. When the Germans marched into Baranowicze, anti-Jewish measures were immediately enacted. Tuvia was forced to clean army barracks, polish boots, and cook for the soldiers. One day, Tuvia’s father was taken to the main square along with hundreds of Jews. They were forced to sit all day, surrounded by German machine guns on all sides, believing they were about to be killed. Tuvia’s father was released at nightfall, and the family decided to leave Baranowicze before things grew worse.

They packed what they could carry into two wagons and fled to Dworec, Poland, where Tuvia’s mother had grown up. In the fall of 1941, the Germans came to Dworec and established a ghetto. Tuvia’s family was forced to move into one room within the confines of the barbed wire area. As towns were being liquidated around Dworec, his family took in orphaned children who had escaped the massacres.

At twelve years old, Tuvia was assigned to a labor brigade where he mined and crushed rocks, loaded them on mining wagons, and pushed the wagons to the railroad yards. The brigade was forced to destroy Jewish monuments at a cemetery and use them to build a bridge across the creek. Tuvia worked as many as sixteen hours a day but was led to believe that his life would be spared, as he was necessary to the German war effort. However, workers soon began dying from hunger. These conditions lasted for over a year until a Polish foreman, who knew Tuvia’s family, managed to relocate Tuvia to a new position as his errand boy just a few weeks before the SS arrived in Dworec.

On December 28, 1942, the SS surrounded the labor camp. Tuvia’s foreman told him to run to the woods. Tuvia escaped, leading a group of workers to a wooded area outside of the camp. After spending all day in the woods without hearing a single gunshot, Tuvia returned to see what was happening. As he neared the camp, he saw inmates throwing themselves on the barbed wire in an attempt to escape, followed by a volley of bullets.

Tuvia fled to the woods. Not knowing what to do next, the group wandered until joining another group who had also escaped. Eventually, as stragglers joined along the way, the group grew to sixty people. That night, they approached a farm to obtain food. The farmer informed them that everyone at the camp was dead. The Nazis tightly enclosed the backs of trucks and rerouted the exhaust pipes into that space. The Jews were asphyxiated and dumped into a mass grave. Eyewitnesses later told Tuvia that his parents were among the first to be killed.

The group of survivors decided to go east and sneak across the front lines into Russia. They splintered off into smaller groups to cross a heavily patrolled German railroad line. Tuvia and his cousin tried to join a group, but no one wanted the young kids. Tuvia, his cousin, and another man chose to go west instead, where Tuvia had heard there were partisans.

Upon reaching the village of Ruda Yavorska, Tuvia was separated from his cousin. He eventually discovered the partisan camp and reunited with his Uncle Benny. For the next twenty months, their shelter consisted of a hole in the ground with an opening in the top for entry, exit, and ventilation. Up to twenty people would lie in the hole and sleep next to each other to keep them from freezing. They begged, stole, and acquired food in any way they could from the local farmers. Attacks by the Germans caused Tuvia’s group to frequently move their camp.

Being young, Tuvia was not allowed to be in the fighting unit. However, he assisted the partisans by performing guard duty and helping around the camp. On occasion, he was sent on assignments with the partisans to ambush the Germans. There were many days of hunger, fear, lack of sanitation, sickness, and enduring the extreme cold. Tuvia survived severe frostbite and typhoid fever. A doctor in the group recommended that his leg be amputated, fearing the onset of gangrene. Tuvia refused.

The conditions became extremely volatile as the Germans were in retreat and neared their camp in the spring of 1944. Tuvia could hear the artillery in the distance. The partisans prepared a well-camouflaged hideout where they spent the last four weeks of the war before they were liberated. The hideout was covered with the scent of garlic to keep German dogs away. On several occasions, the Germans stood directly above their hideout but did not discover them.

In the summer of 1944, Tuvia was liberated by the Russian Army. For thirty days, he served in the army by guarding German POWs on a train en route to Siberia. In the spring of 1945, he lived in Lodz, Poland, with his Uncle Benny. Intense antisemitism in post-war Poland led Tuvia and his uncle to join the clandestine movement that was journeying to Palestine. They abandoned what little they had and joined the other refugees traveling through Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Austria. They ended up in the American-occupied zone of Austria, where they spent the next fifteen months in Displaced Persons camps.

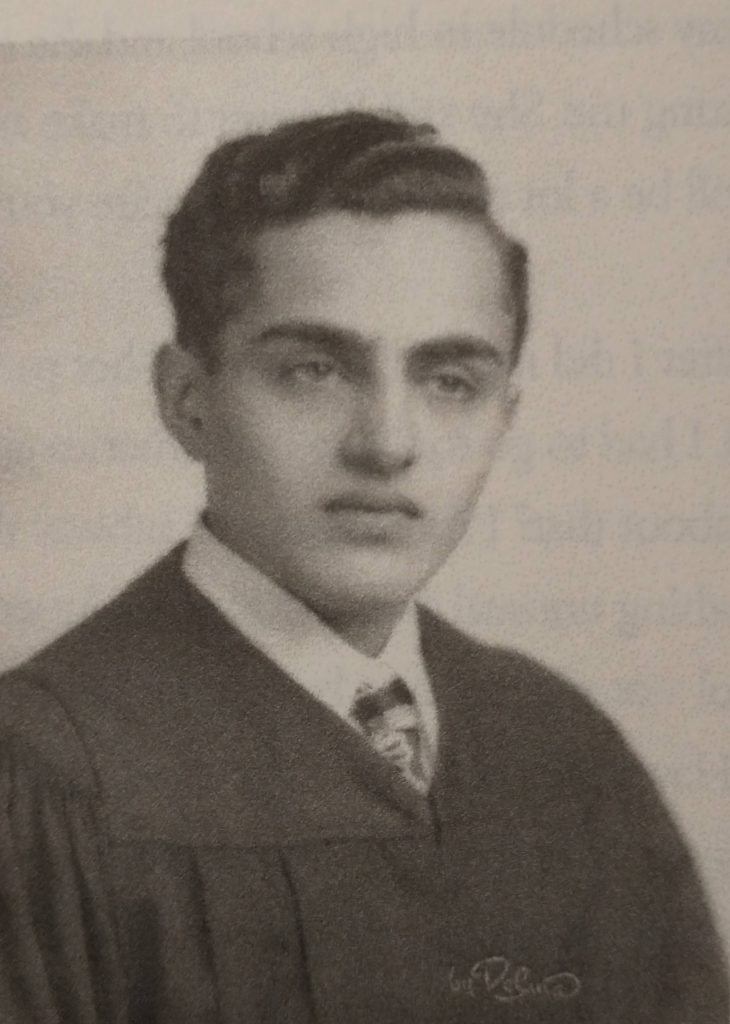

Tuvia’s great-aunt decided he should not languish in a Displaced Persons camp awaiting the possibility of going to Israel and instead should come to America. In 1947, at the age of seventeen, Tuvia (now Ted) immigrated to New York, where he lived with his Great Aunt. He attended the local public high school while also working to contribute to his upkeep. He was able to learn English and graduate in three semesters even though he had not been in school since 6th grade.

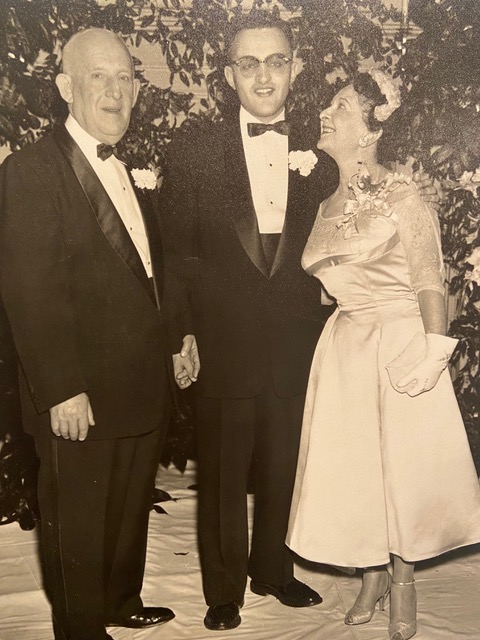

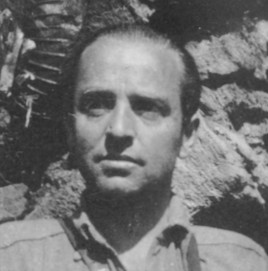

When his great-aunt died, Ted’s uncle in Memphis invited him to come south. Ted graduated from Memphis State College after three years and was promptly drafted into the U. S. Marine Corps where he served for two years during the Korean War. After his service in the Marine Corps, Ted worked in an accounting office and went to Southern Law University. He received his CPA certificate, graduated from law school, and passed the bar.

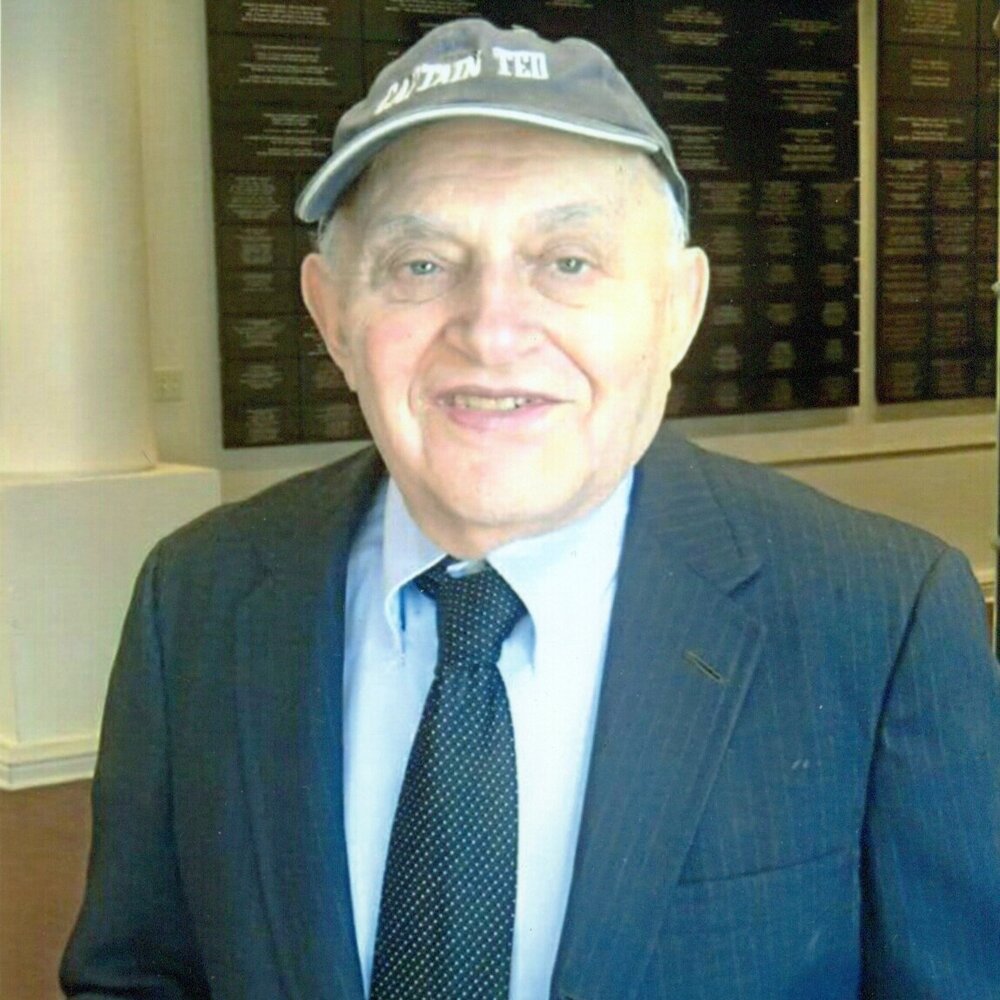

Ted lived in Memphis, TN with his wife Jocelyn. He has five children, seventeen grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren. He was a practicing attorney and CPA. He helped establish and support, the Memphis Hebrew Academy, and provided the opportunity for all his children and grandchildren to receive a Jewish education, amongst the many contributions he has made to his community and abroad.

Ted has shared his testimony with the US Shoah Foundation and recently wrote about his experiences in his book, Run to the Woods. Further information on Tuvia’s incredible life story can be found on his website: tuvyastory.com.

Ted passed away on September 17, 2022, at the age of 92.