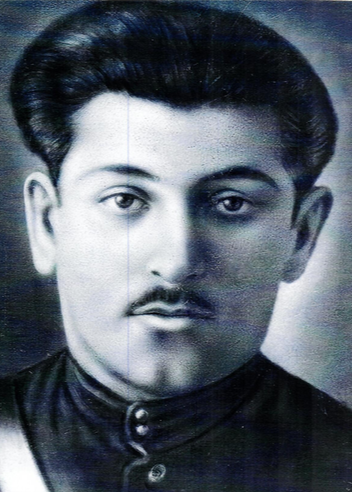

Velvel Yanson was born on May 30, 1920, and grew up in Lubcz (Lubscha), Belarus. He was the son of David Yanson and Chasia Yankelowitz Yanson. Velvel had two sisters, Grunya and Henya. When he was 19 years old, his life changed forever.

In August 1939, upon hearing that the Germans were preparing to attack Poland, Velvel realized something bad was brewing. “I go home with a heavy heart as though we’ve been warned that a terrible storm is moving in our direction,” he said. At this point, the Russians occupied most towns in eastern Poland including Lubcz. The synagogues were closed and used for storing crops. Life went on under Cossack rule until 1941 when the Germans began to bomb the cities. Velvel, as well as many other young men, was called up to join the Red Army. However, the Germans attacked and the whole group dispersed and he ended up in the Pereshunke Ghetto (Novogrudok). When the slaughter began, Velvel was among those chosen to die. Under a hail of bullets, he decided to run and escaped to Lubcz, but found all the Jews in a ghetto.

After hiding with relatives for a while, Velvel returned and was forced to labor for the Germans. He avoided death in the slaughter of Novogrudok’s Jews in December 1941. He got word that 500 people, including women and children, his sister Grunia, her husband David, and their two small children were all forced together in a barn and burned alive. At this point he said, “A fire was kindled in my heart, a fire of revenge. I swore that my hands would not rest until I avenged the beastly death of those dearest to me, whose innocent lives were stolen from them.”

Velvel managed to escape from the ghetto with three other people. He went to find his other sister Henia who begged him to take her out of the camp at Dvoretz. He promised to come back for her as he had no idea where he was going or what would be. When they attempted to join the Orlianske Partisan unit, the Jewish partisans of that unit rejected them and told them to look elsewhere. Eventually, they joined a group of Russian Partisans.

After a period of training, they were placed in a unit consisting of 300 fighters and he was given a gun. Knowing that the next bullet flying by could be the end of his life, he asked for permission to go back and get his sister Henia. However, he was too late. The Germans had destroyed the camp and killed everyone. This increased Velvel’s desire for revenge and he continued to fight with the partisans, facing fierce fighting against the Germans. Eventually, he was appointed commander of a group of 60.

Life for Velvel and his fellow Jewish partisans was not easy within the Russian group. Soon they noticed that antisemitism was rampant among the Russian partisans. At first, they were welcomed, but after an attack by the Germans, where a number of Russian partisans were killed, they blamed the Jews. Life with this group became unbearable. Velvel and another partisan, Ichik Levin, separated from the Russian group and found refuge in a small Jewish camp.

Velvel became ill with Typhus and was cared for by the Jewish refugees in the camp. The Russian group arrived at the camp, found Velvel and his friend, and accused them of being deserters. However, upon explaining that Velvel had been ill with Typhus and was planning to return upon recovering, they accepted their excuse. They rejoined a Russian unit, but antisemitism was rife and many Jews were slain by the Soviets.

Eventually, Velvel and Icihik decided they had had enough. The Jewish partisans requested that they form their own unit. This way they could be independent and protect fellow Jews in the camps. They had enough arms and supplies that they could use or procure. Their commander gave them permission to go off on their own. They united with a group of Jewish partisans led by Senke, a Jewish man from Minsk. Velvel served as his lieutenant. The unit survived for about three months until a group of Russian partisans killed many of them. In the ensuing battle, Senke, and many more from the unit, was killed. The survivors were arrested, tried, and sentenced to death. Velvel, as the second in command, was to be shot.

As he was led into the forest by a Russian partisan, the man decided to slap him instead. Velvel, in turn, tried to choke the man who then told him he was a fellow Jew, but the Russians did not know his true identity. He led Velvel further into the woods, shot his rifle in the air, and then told him to flee. Velvel rejoined his men and fled to the Lipiczansky forest and joined another otriad.

In the meantime, Leah Bedzowski, her mother, and her brothers had joined the Bielski group (1942). At one point, Tuvia Bielski told the group that they had to go their separate ways due to an oncoming German onslaught. As the German army advanced towards them, the Bedzowski family became separated from the rest of the group. Leah, her mother Chasia, her sister Sonia, and her brothers, Charles and Benny, kept together with a small group of people. “We felt helpless,” she said. “We didn’t know where to go, so we all sat under a tree.” Unsure of what to do, they were sitting there when a group of young Jewish partisan men found them. One of the men was Velvel “Wolf” Yanson.

Velvel and his group came across these people and asked them why they were just sitting there and had not run away. The men were crying and the children were terrified: everyone was afraid. They told Velvel that everyone had already escaped, but they didn’t know where to go. In the unit that Velvel was part of, they were not to take anyone into the group or separate themselves from the group. But seeing that these people did not know what to do, he decided to stay with them and find a safer place. He knew that the Germans were not too far away and that they needed to keep going. He warned them that if they stayed, they would surely be killed.

Included in this group were the Druk family, the Berdowski family, and Leah and her family. When Velvel saw them there helpless, he knew that this is where he had to be. He left his group, took his rifle and his pistol, remained with them, and led them to a safer place. He stayed with them for a few months. When everything quieted down, he rejoined his former group and they began negotiations with Bielski. They combined their forces but remained a separate group. When Velvel found out that Tuvia Bielski was trying to gather everyone together again, they rejoined the group. Velvel became the protector of the Bedzowski family even while they were amongst the Bielski group. Eventually, Velvel and Leah fell in love and they were married under a chuppah among their fellow partisans in the forest.

Velvel and some of his comrades combined forces with the Bielski group and organized a unit name “Orzshenikitzshe.” This unit became the strongest force within the Bielski unit. Bielski’s group became well-known in the area because of their undertakings. They blew up trains, roads, bridges—anything that could serve the Germans. Velvel, with another man, would often do lookout duty. If there were people who should not be there, such as Germans and collaborators, they were killed. He also helped blow up trains, bridges, and German offices. He would be gone for weeks at a time. He became known as “Velvke the Pulimiochik” – Wolf the Machine Gunner.

In 1944, soon before they were liberated by the Russians, there was a huge firefight. Velvel had his machine gun with him as he lay perched in a tree, trying to stave off the onslaught. Many people were killed as the Germans attacked. Then suddenly, it was over. The Bedzowski family, under the wing of Velvel, stayed with the Bielski group throughout the war until they were liberated.

The family returned to Lida where they found a room and work in the town. Once again, the Russians wanted Velvel to be a fighter. Leah hid him in a cellar for about a month until she was able to make him a passport to get him out. He went to Bialystok, where the family eventually joined him, and then they went to Lodz. They wanted to go to Israel but were told they would have to first go to Greece. The couple fled the country through Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Austria until eventually crossing the Alps into Italy, where they remained for four years at a Displaced Persons camp in Torino, Italy.

During this time, their first child was born. Velvel wanted to go to Israel and join Ben Gurion in the fight for the land, however, they could not go because they had a child. Leah told Velvel to go without her and she would meet him later. He, however, would not leave her and the baby. After all the horror and fighting and loss of his family, he now had a new family. In 1949, the family emigrated to Montreal, Canada where they settled and raised three children

Velvel, through sheer will and the desire to survive, risked his life many times to fight the Germans and the Russians. He managed to survive against tremendous odds after having been shot, coming down with Typhus, and being scheduled for slaughter numerous times. He took the Bedzowski family under his wing and, as Leah said, “It is thanks to his fortitude and strength that my mother Chasia, brothers Chonon (Charles), and Benjamin, as well as the other families whom he encountered under the tree, were all saved. If it wasn’t for him, my family would have perished and the Bedzowski/Bedzow name would have vanished for eternity.”

The desire for vengeance was over. He had done what was needed to survive and to protect his new family.

Leah Bedzowski Johnson’s story is featured on the JPEF website.